Félix Betrán learned his trade in the Mad Men era in New York. He worked for some of the biggest and hottest advertising agencies at the time and his colleagues included design icons such as Herbert Bayer and Milton Glaser. But in the sixties he was drawn back to his home country of Cuba, where he put his skills at the service of the revolution.

Félix Beltrán created truly revolutionary graphic design and is considered one of the most influential designers in Latin America. He died in Mexico on December 28, 2022. Here you can read an interview with Sonia Díaz and Gabriel Martínez, who published a great monograph on Beltán's work a year earlier.

One is sometimes amazed at the eventful biographies that older generations had, and Félix Beltrán's life also seems more like something out of a movie than reality. At the age of just 15, the Cuban was discovered in New York by the head of the renowned advertising agency McCann Erickson. He was an assistant to Herbert Matter at Yale University, as a fellow of the New School of Social Research he got to know Theodor Adorno, Herbert Marcuse and Erich Fromm and as an art director he was later promoted by Bob Gill and worked with design greats such as Herbert Bayer and Milton Glaser. In the early 1960s, he returned home to support the revolution with his resources.

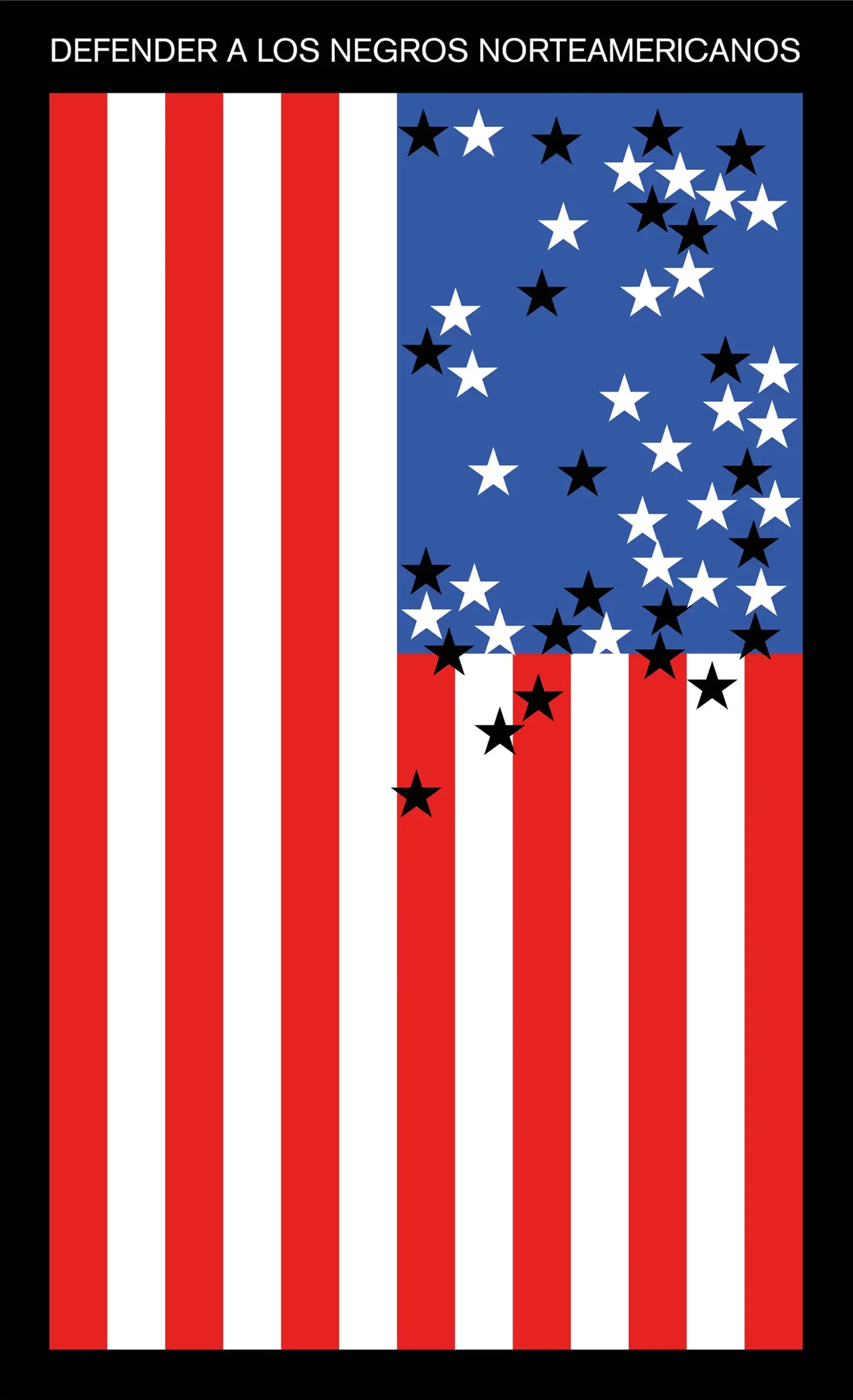

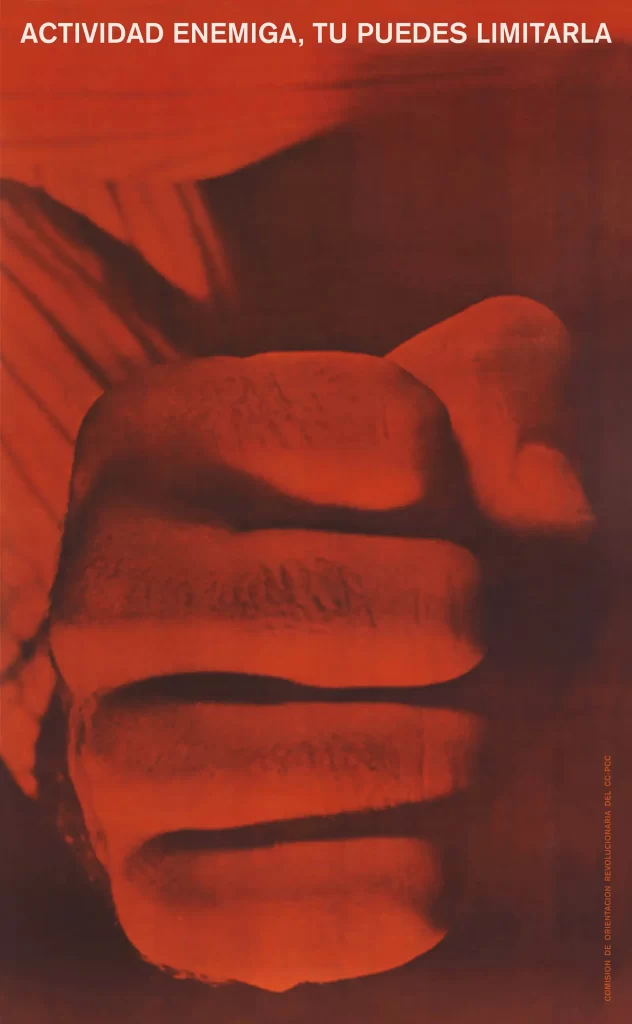

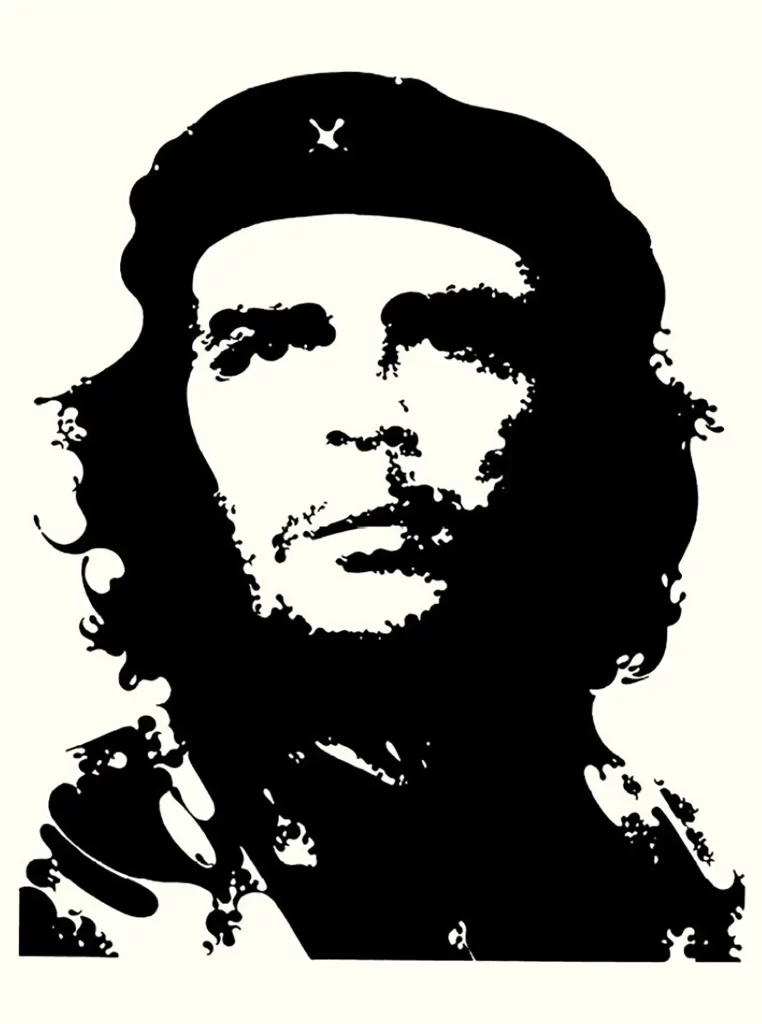

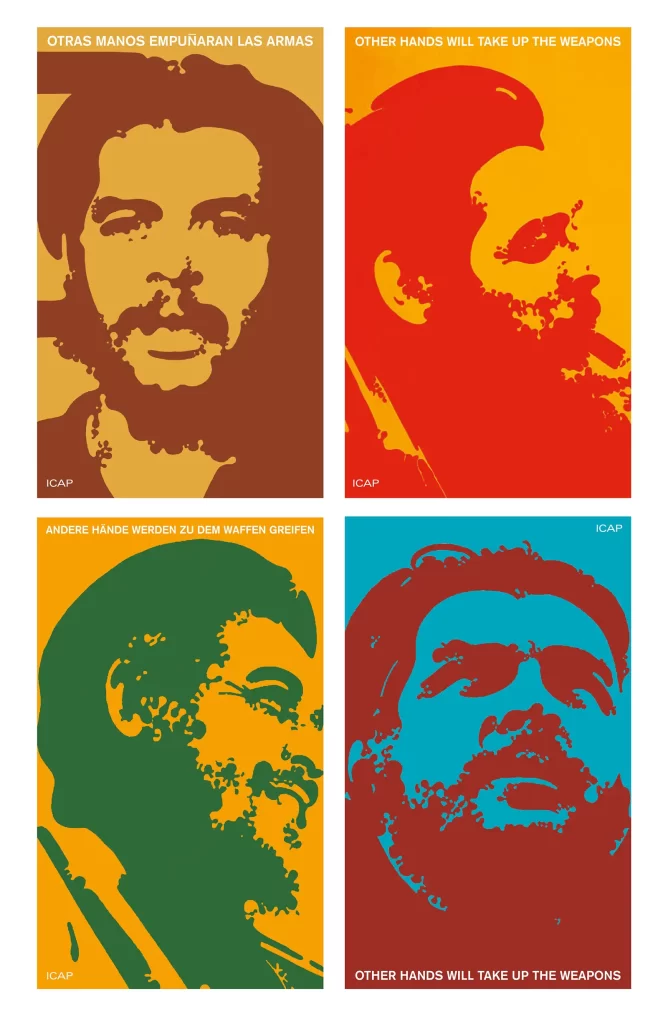

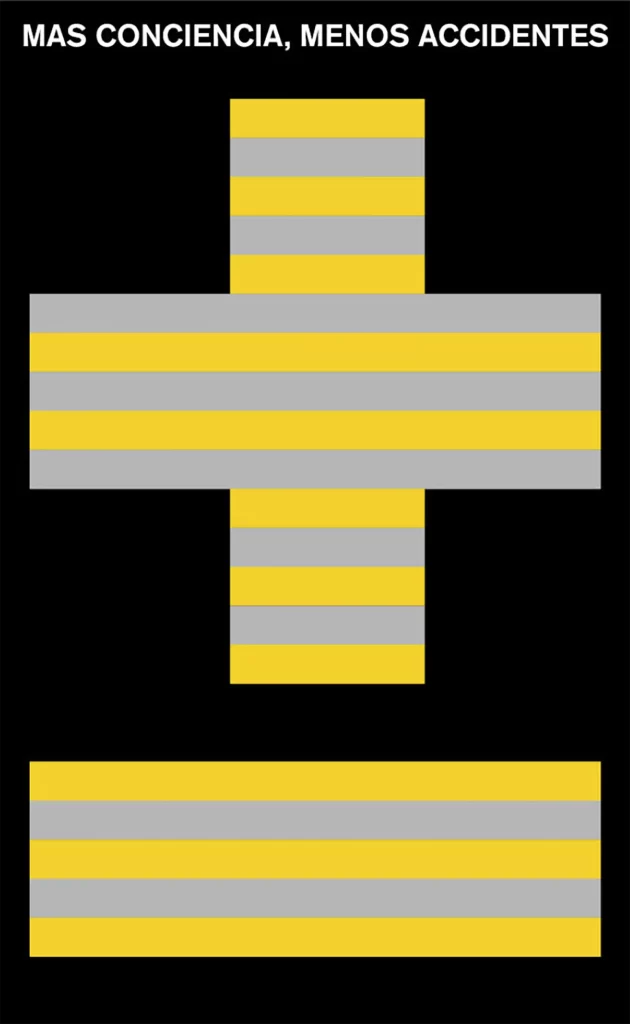

In Cuba, Félix Beltrán developed his very own style based on his profound knowledge of design and communication and influenced by restrictions in the country. His mantra "simplify, simplify, simplify" was due to the lack of resources in Cuba, but above all arose from his design philosophy of communicating what is really essential. Félix Beltrán's work is highly condensed visual communication and is still exemplary today for what graphic design is and, above all, can be. Sonia Díaz and Gabriel Martínez, whose biographies are just as illustrious as those of Félix Beltrán, documented the work and above all the teachings of the great Cuban designer in the monograph "Visual Intelligence".

What sparked your interest in Félix Beltrán's work?

Sonia Díaz and Gabriel Martínez: His insights into "design in a social sense" and his capacity for synthesis and graphic precision. From the very first moment, we were fascinated to look behind the work and find out how those experts in graphic design and visual communication that we admired the most really think. In our extensive library there are many books dedicated to various practical, theoretical and pedagogical aspects of European and North American authors, Latin America is underrepresented. On the other hand, in books on the history of graphic design, Félix always appeared as a prominent representative, even if he was only ever listed with the same two posters and a few logos.

The key moment for us came in 2005, when we had the opportunity to meet him in person and establish a close relationship that resulted in various exhibitions and lectures. In this way we discovered his work, much of which is unknown, and felt that it was important to create a monograph that would bring together all his work and contributions to design theory and save them from oblivion.

Designers such as Wim Crouwel and Milton Glaser held Félix Beltrán in high esteem, but for many younger creatives he will be a new discovery. Why are Félix's designs and teachings still so relevant today?

The importance of his work lies in the fact that Félix is a very timeless designer, but he is also very much of his time and has always remained true to his ideas without being influenced by fashions or trends. His work is very didactic and easy to understand. His motto "simplicity of content means simplicity of form" is particularly useful today, as we live in a world of a constant flow of information and misinformation.

The ethical approach is also important. Lesson 29 in the book is instructive here: "Explore your strengths, improve your weaknesses." In our opinion, Félix suggests that while we should act, we must not forget that our work has meaning. Creativity is not an end in itself, but an answer to a specific problem. Or in other words: theory is the result of clearly defined goals.

Félix comes from Cuba, but his influences came from all over the world. Can you tell us something about his life and his career as a designer?

Beltrán studied at the renowned School of Visual Arts in New York from 1956 and was a student of Bob Gill. As a fellow of the New School for Social Research, he had the opportunity to get to know Theodor Adorno, Herbert Marcuse, Erich Fromm, Rudolf Arnheim, Alfred Schütz - a student of Edmund Husserl - and Fred Kersten. And in New York he also worked with such illustrious figures as Herbert Matter, Herbert Bayer, Louis Dorfsman, Paul Rand, Ivan Chermayeff and Milton Glaser. Another designer with whom he had a close friendship was the Japanese Shigeo Fukuda.

He was influenced by such diverse things as Swiss typography, American modernism, Italian and Japanese design, abstract art and pop art. He also always emphasizes the importance of American advertising, where text was extremely important, such as in the work of DDB / Doyle Dane Bernbach. But undoubtedly the influence of Bob Gill, whose outstanding student he was, was decisive for him because of his ability to synthesize and his graphic strength.

Félix himself said: "It was very difficult to concentrate fully on design when there were no colors, no paper and no electricity."What was it like to work in Cuba from the sixties onwards?

Félix returned to Cuba in 1962, there were no resources and the designers worked with the colors that were available, creating designs that were subtle and symbolic. Félix also says that the posters had to be simple, not out of conviction, but because nothing else was possible.

As far as Cuba is concerned, the use of color is a very important element, as well as high contrast photographs in which the shadows were eliminated, which made printing easier. As a consequence of the technical limitations, a style was created that was defined by the use of simple planes, bold colors, sharp outlines and shapes that were in harmony with what could be printed.

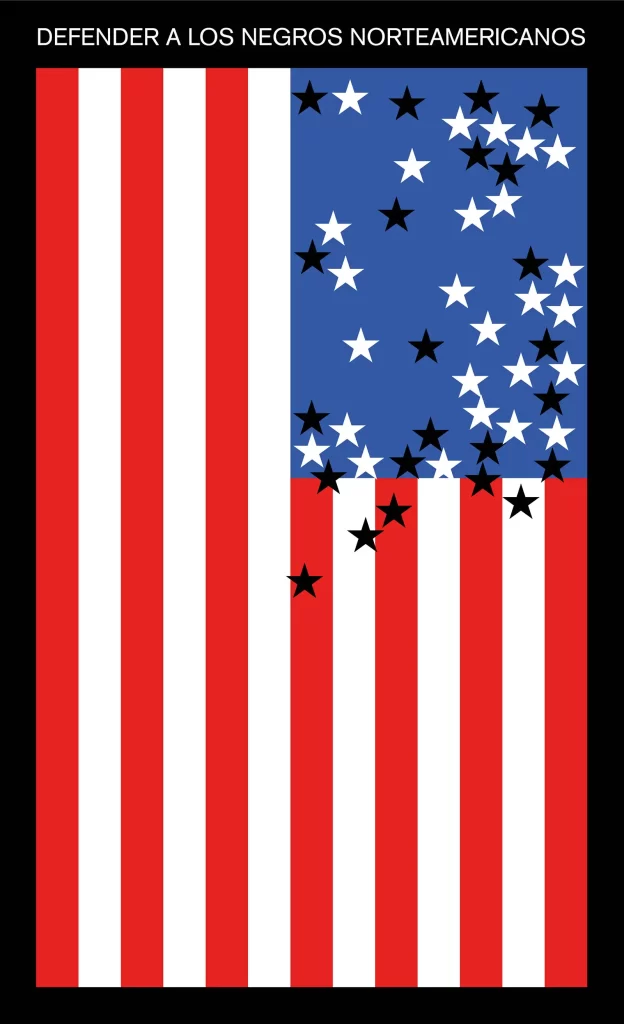

Félix was at times the chief designer of the propaganda department of the Communist Party in Cuba and developed expressive motifs with calls to save electricity or oil, for example. Was he a political person, a political designer?

When he returned to Cuba, he began to work for the revolution and created simple, direct and symbolic designs. Communication should be in line with the reality of underdevelopment and reflect the new social perspective. For in Félix's opinion, in a socialist state, where the state and the people are one and the same, every poster, no matter what subject it deals with, is always a social poster. Politics is synonymous with culture and no design can be apolitical or devoid of culture.

According to Félix, the Cuban design of the time made it possible to recognize the goals, ideology, economic and political perspectives of the revolution. Because a new society was being created in Cuba.

He himself always showed himself to be prudent, precise, systematic and responsible in his conclusions and had a vision of design that was inextricably linked to the revolution. The way he saw the revolution emerged directly from his design practice. From our point of view today, he appears as a 'catalyst of clarity' who was always at the social, political, technological and cultural forefront.

However, it is also true that towards the end of the seventies he felt that the revolution was not working, and this sense of failure created an enormous emptiness in him. The circumstances of the revolution and its increasingly clear contradictions led to a profound sense of frustration, which eventually prompted him to leave Cuba and move to Mexico.

Félix also taught for many years. In your opinion, what were his most important contributions to design teaching?

In the seventies, he wrote three groundbreaking books that are milestones in the history of Ibero-American design. These publications were written at the same time that Félix was creating his work and achieving fame as a lecturer at various schools and universities in Cuba and Mexico. On the other hand, they manifest his profound understanding of social and political action. He avoided lectures as much as possible, preferring rather a kind of maieutics, a Socratic teaching method based on a dialogue between teacher and student to reflect on his work.

If we had to highlight his greatest didactic contribution, it would surely be "letragrafía", a concept he coined that says that words should not contradict their content and that letters have a formal value that implies different associations. Letters are forms and refer to constructive schemes, to organizational structures and spatial compositions that reinforce and emphasize visual codes of social communication.

After seeing and researching so much, which of Félix Beltrán's works do you like best?

It's hard to say, we love all of his work. But there are two works that we didn't know before and that have become favorites. They are the poster "Towards the study and deepening of Marxism" (1968) and the cover of "System of Marxist studies of the MININT" (1972), because they are perfect examples of Félix's philosophy: simplify, simplify, simplify.

Developing solutions through design is perhaps more important today than ever before and that is why we believe that it is very fortunate for students and us as designers to be able to draw on the knowledge of designers who have already done so much groundwork.

Félix Beltrán: Visual Intelligence

Sonia Díaz, Gabriel Martínez

Optik Books, www.optikbooks.de

360 pages, text in English

ISBN 978-3-9822542-3-4

38,- Euro, 44,- $

This interview was published at the beginning of 2022 in issue 01.22 of Grafikmagazin with a focus on "Illustration".