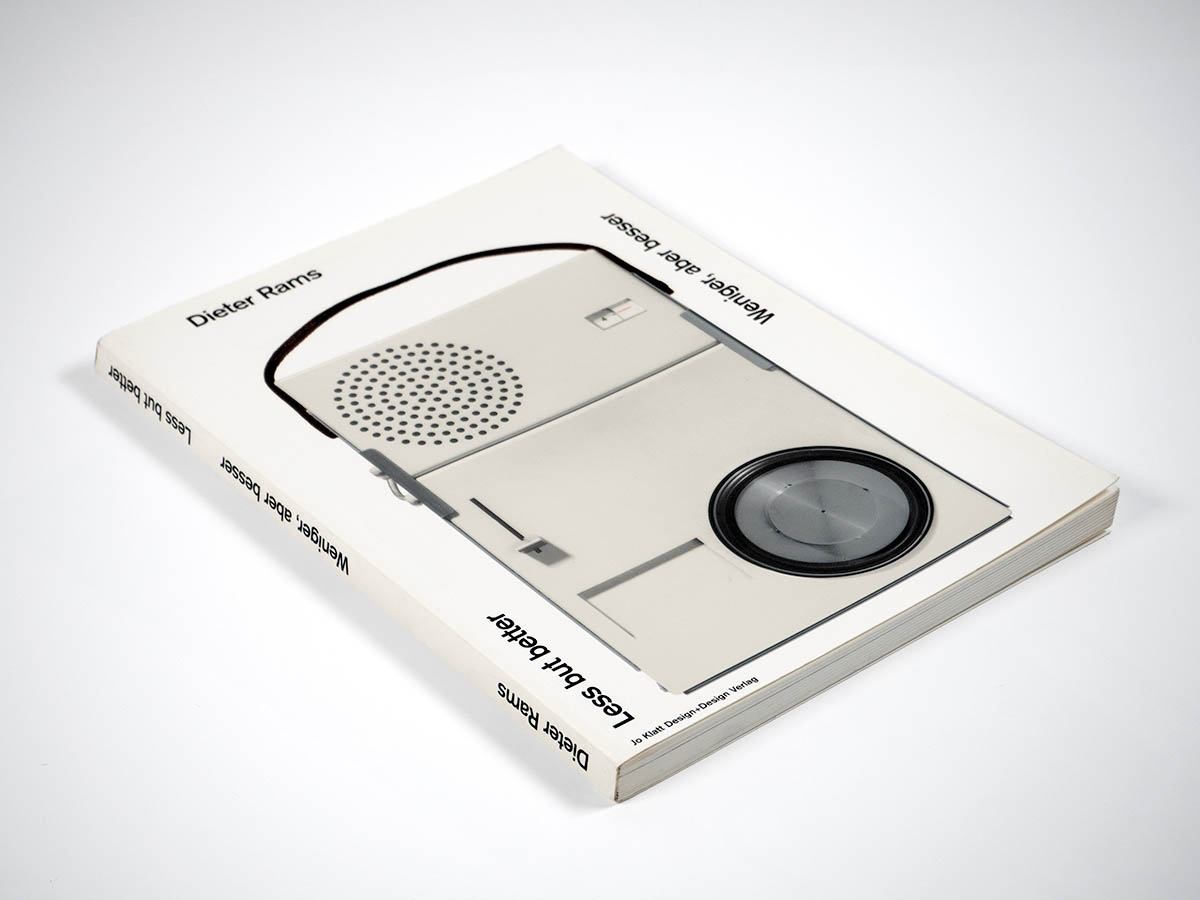

"Simple is better than complicated, light is better than heavy and the obvious is better than the sought-after." These are the demands that Dieter Rams, one of the world's most renowned product designers, made of good design and the standards by which he always measured his own creations.

Some things are simply too good for the drawer. In 2004, Dieter Rams gave an insight into his work in an interview with Christine Moosmann for Design Indaba Magazine. What makes good design and what designers should pay attention to is still just as relevant and contemporary today ...

Dieter Rams is one of Germany's best-known industrial designers and is regarded as one of the great representatives of functionalism. Over the course of his decades of work, he has received numerous awards. For example, the Royal College of Arts in London named him "Royal Designer for Industry" and awarded him an honorary doctorate. He received the "World Design Medal" from the Industrial Designer Society of America and his work can be seen today as an integral part of design collections in museums such as the MoMA in New York, the Victoria & Albert Museum in London and the Stedeljik Museum in Amsterdam.

Born in Wiesbaden, Germany, in 1932, Dieter Rams came into contact with the principles of economic design at an early age. In his grandfather's carpentry workshop, he was able to observe how great care in the choice of materials and workmanship led to a simple but functional and useful design. These experiences had a lasting influence on Rams. They prompted him to constantly strive for simplicity and simplicity on the one hand and to learn a design profession on the other. He initially chose interior design and in 1953, after interrupting his studies for a few years to do an apprenticeship as a carpenter, Rams graduated from the Wiesbaden Werkkunstschule with a diploma and distinction. While still a student, Rams became increasingly interested in architecture - the foundation for this was laid by the director of the Werkkunstschule, Prof. Dr. Dr. Söder, who specifically promoted a combination of design and architecture within the school framework.

After completing his studies, Rams initially worked as an architect and was recruited in this role by the Braun company in 1955. His unmistakable career as a designer began the following year, as Dieter Rams' career and great success as a product designer remained inextricably linked to the fortunes of the Braun company for many decades.

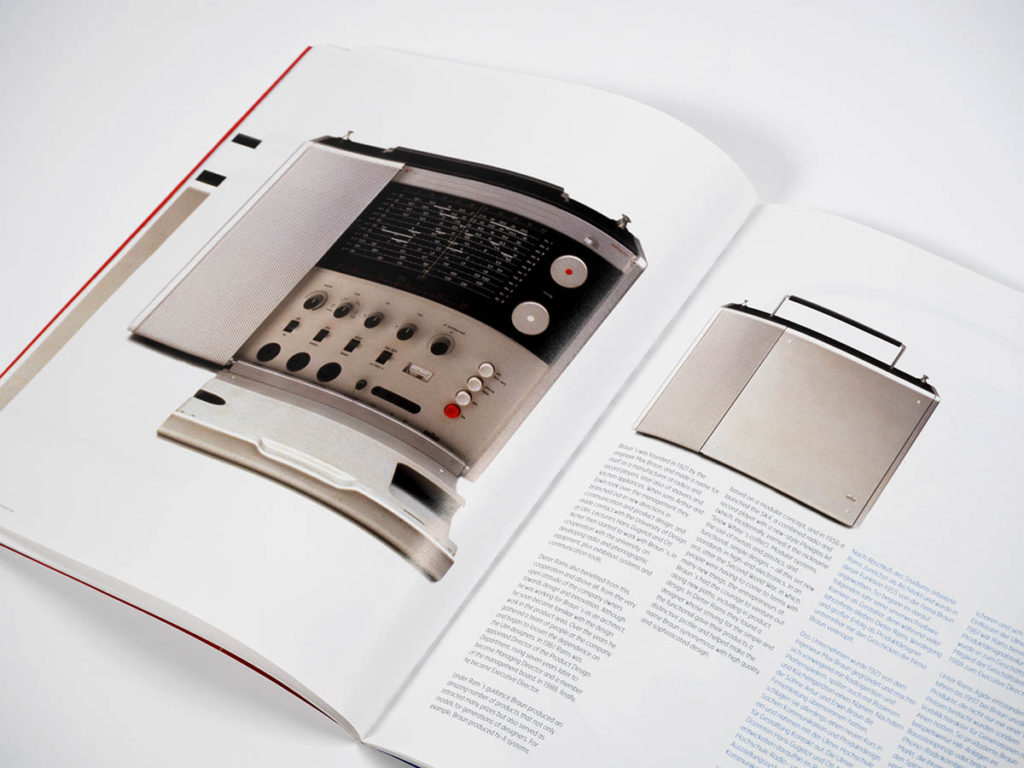

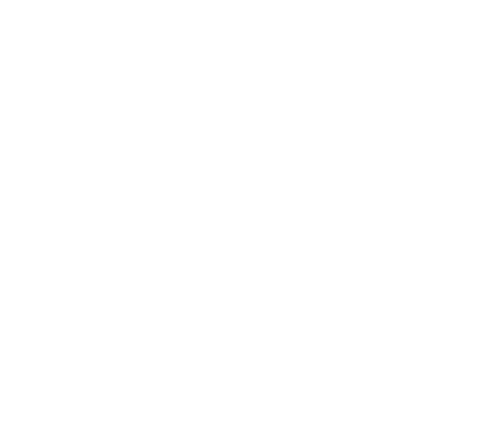

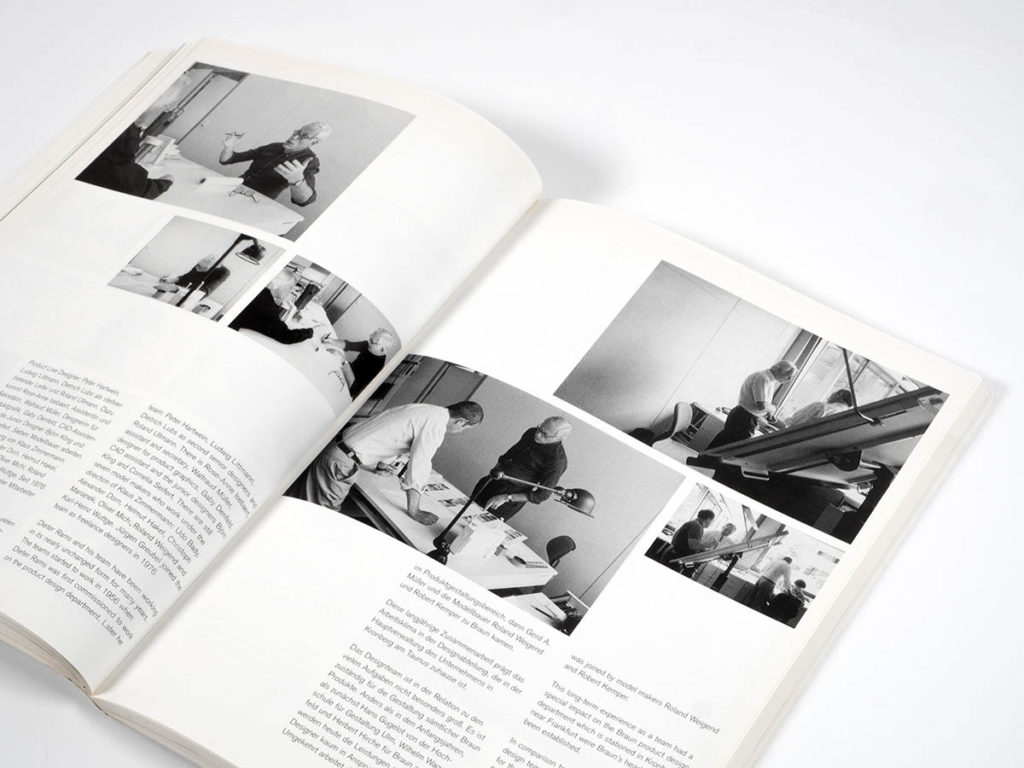

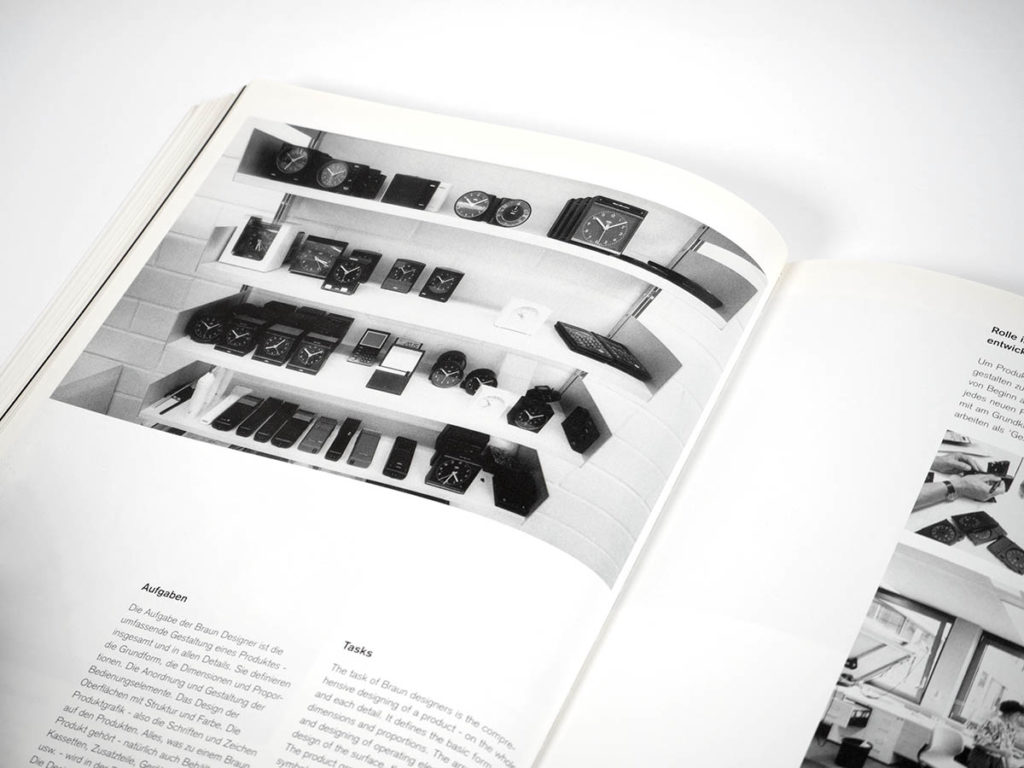

The company was founded in 1921 by engineer Max Braun and made a name for itself primarily with radios and record players, and later also with shavers and kitchen appliances. However, after his sons Artur and Erwin Braun took over the management of the company, they embarked on a new course in communication and product design and contacted the Ulm School of Design. The Ulm lecturers Hans Gugelot and Otl Aicher then developed radio and phono equipment as well as exhibition systems and communication media for Braun at the university.

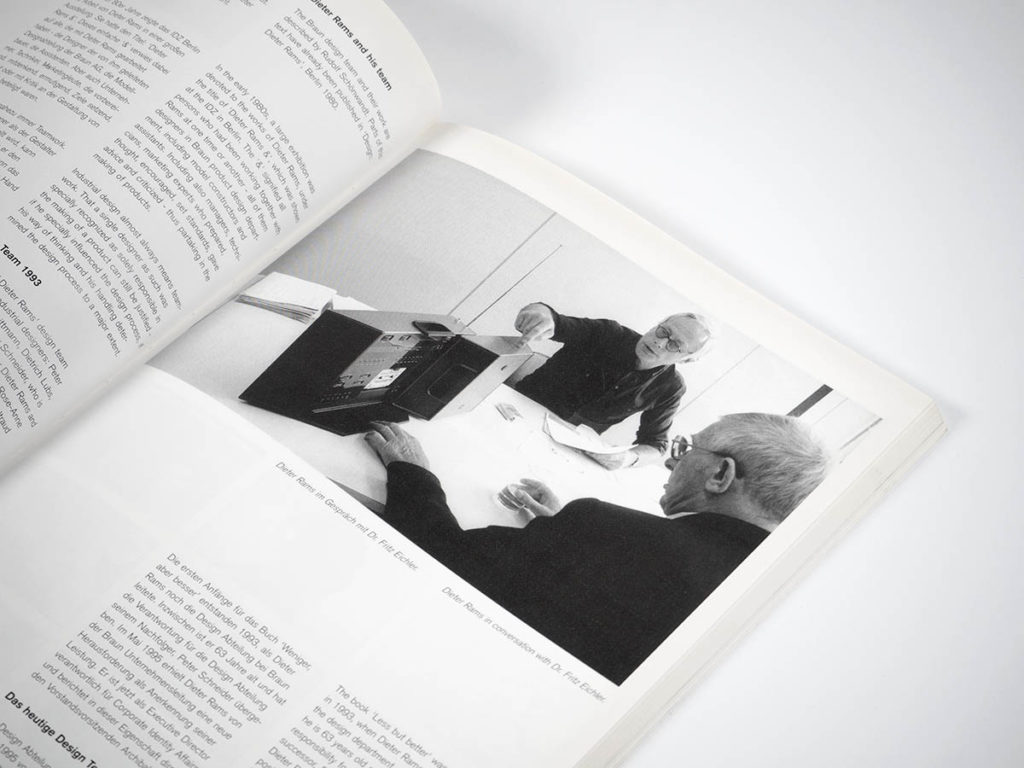

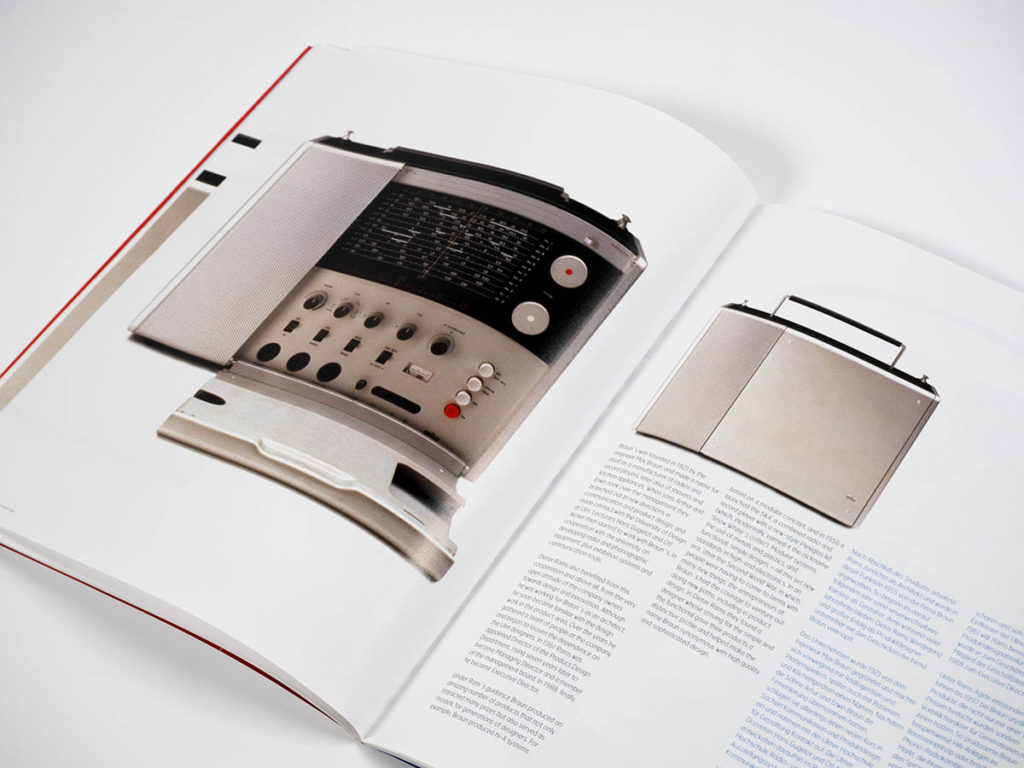

Dieter Rams also benefited from this collaboration and, above all, from the fundamental openness of the company owners when it came to design and innovation. Although he worked as an architect for Braun, he was soon entrusted with design tasks in the product area and over time had the opportunity to gather his own employees around him and gradually free himself from the influences of the Ulm University of Applied Sciences. By 1961, Rams was already head of the product design department, seven years later he was appointed managing director and member of the management board and finally in 1988 he was appointed executive director.

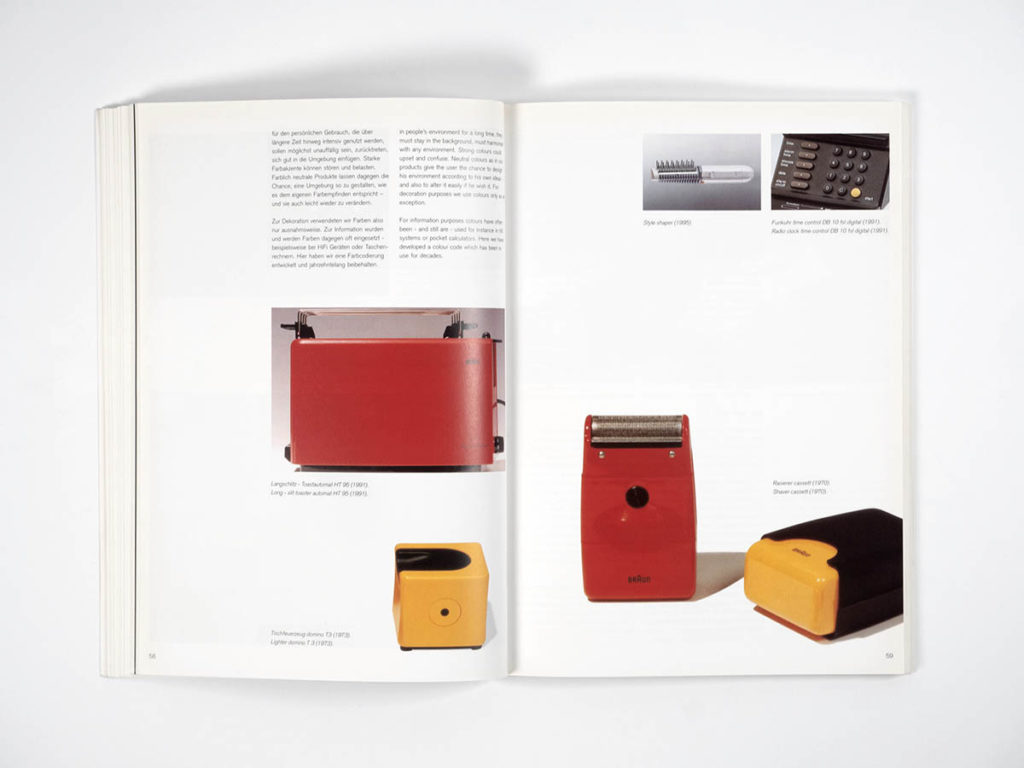

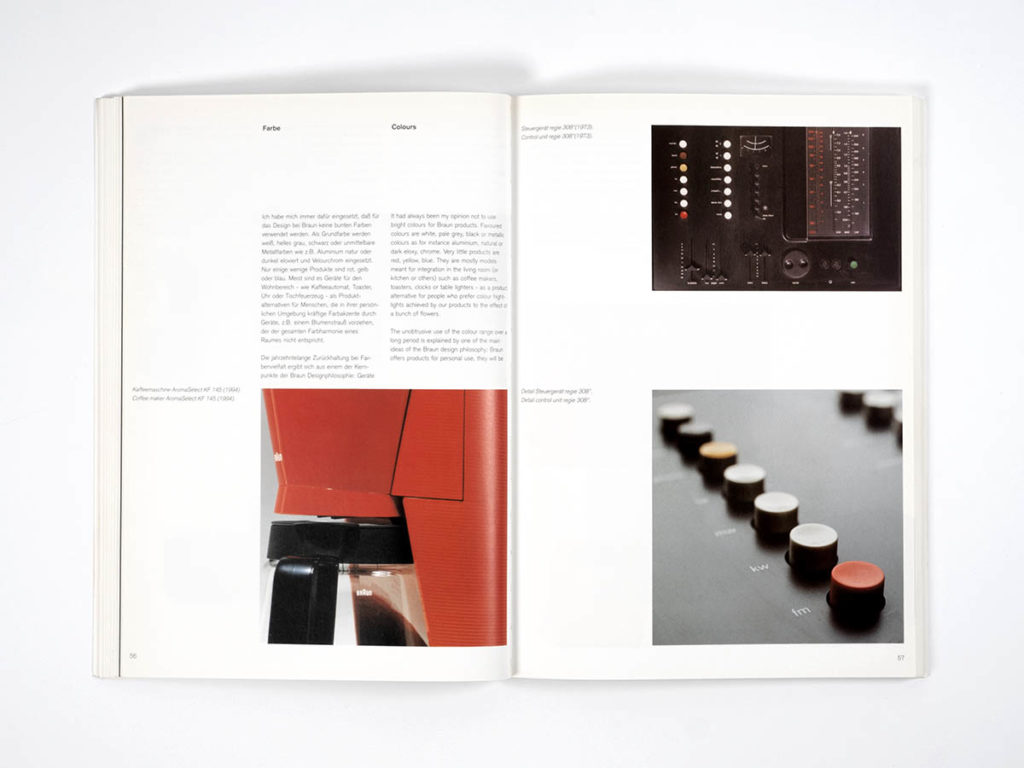

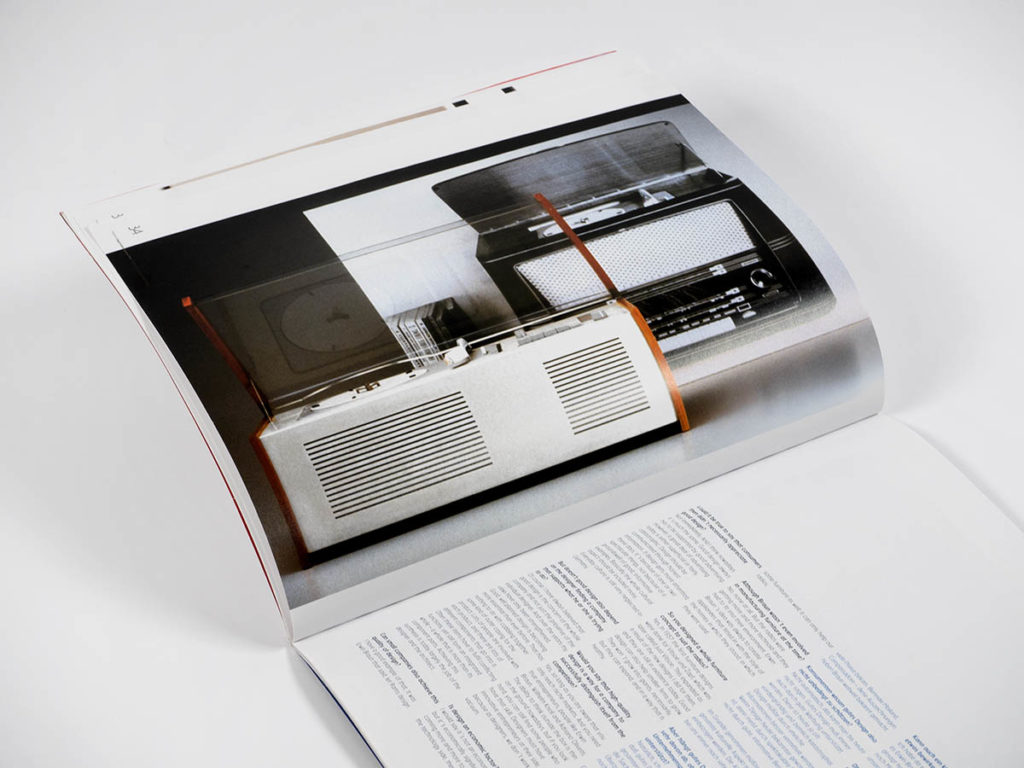

Under Ram's aegis, countless products were created at Braun in the years up to 1997 that not only won numerous awards, but also set an example for generations to come. For example, Braun produced hi-fi systems based on the building block principle or launched the SK 4 phono radio combination on the market in 1956, which was nicknamed "Snow White's coffin" thanks to its innovative Plexiglas lid. Modular systems, the materials metal and plastic, a function-oriented, minimalist design - all this set new standards for high-quality electronic products. At a time when society inevitably had to cope with many changes after the end of the Second World War, the Braun entrepreneurs had the courage to leave the beaten track in product design too. In the person of Dieter Rams, they found a designer who, with his striving for simplicity and simplicity, gave their products an unmistakable shape and made the name Braun synonymous with high quality and sophisticated design.

For Design Indaba magazine, Dieter Rams talked about his standards for good design, what designers should look out for and how he sees the importance and future of design.

Mr. Rams, was the general mood in Germany in the post-war period also reflected in design?

Yes, this period was a time of beginnings. We were all fed up with the hypocrisy of the previous years and in this time of change, the climate was naturally favorable for cleaning up in the truest sense of the word. And of course the re-founding of the Ulm School on the basis of the Bauhaus was also decisive and exemplary. As I said, my intention was to get away from this mendacity in design. And not just in design, in architecture, everywhere.

Then in 1955 you came to Braun . ..

Yes, and in the first two or three months I was more entrusted with architectural tasks. Very quickly, however, I was also given industrial design tasks. The first was the legendary Snow White coffin, which was designed together with Hans Gugelot and the Ulm University of Applied Sciences.

The radios made Braun world-famous, what effect did that have on the company?

They helped to make Braun better known. Not that they were a financial success, you can't say that. They had to be supported by other products within the company.

In other words, the money was actually earned with other products?

Yes, the butter on the bread at the time was, for example, the so-called "hobby flash", the first flash units that even amateurs could afford. Later, household appliances were added and it wasn't until the early sixties that razors were introduced. But the whole radio business, for which Braun was known, was always in the red. However, the redesign of these appliances helped to make Braun world-famous.

The devices were unusual and attracted a lot of attention, but they didn't sell particularly well?

There were too few opinion leaders. At that time, people first had to be converted to good design. A lot was done to present the products and make them better known. But the main thing that helped was that Braun won a lot of awards very quickly. The Milan Biennale, Compassadore - these awards have made Braun known worldwide.

So consumers don't necessarily appreciate good design?

Not automatically, you can't say that to this day. Good design must always be supported by good advertising. Nowadays, advertising is often superficial and quite disastrous. Design should be better communicated through honest information. When design has become better known today, it is usually through spectacular things, not through good, informative examples.

Basically, the whole cultural aspect should be included more. Everyday culture is still very much neglected in our country.

But doesn't good design also depend a lot on whether a designer finds a corporate partner who supports them?

Of course, I have always been convinced that good design is a matter for the entire company and not just for individual designers. This conviction has become even stronger over the years.

Good, well-planned design is becoming more and more of a prerequisite. This has nothing to do with the quick, non-committal dressing of a product. Many people work on every product and it usually contains a large number of different components. Things should fulfill often contradictory functions and yet be a whole - a whole that is more than its parts. Achieving this synthesis is largely the task of designers and architects today.

Can even a small company make a difference?

I have a good example. I have Erwin Braun to thank for the fact that he said, let Rams make furniture on the side. That can only help our radios.

Even though Braun didn't make any furniture back then?

No, no, zero. But the radios had become more technical and had to fit into the environment. Erwin Braun's concern was always to create devices that were related to the respective interior design and the houses in which they were used.

So you designed an entire furniture concept that matched the radios?

Yes, the first furniture designs for the company Vitsoe and Zapf, later Vitsoe, were created in 1957. This company grew and became big with the new designs that I created for them and still exists today.

So even smaller companies can become big with design. Not insanely big, but they can grow and, above all, grow healthily.

So you can successfully stand out through high-quality design?

Yes, if you realize that you can only reach niches. And you need entrepreneurial personalities like Erwin Braun, Wilhelm Knoll or Adriano Olivetti. They are in short supply today, but they still exist on a small scale, those people who think outside the box.

Designers need to have innovative entrepreneurs at their side, because as designers we don't work in a vacuum.

Is design an economic factor?

I would say it is not an economic factor, but it is economically significant.

Design is becoming increasingly important. Since the available technologies are now almost the same for everyone, the only remaining differentiating factor is design. And design has become more popular, although there is still much to improve in terms of handling and utility. There is still a lot to do to make things more comprehensible and easier to use. I also pick up on this point in my theses: "Good design makes a product easier to understand."

You yourself trained as an architect and yet became world-famous as a product designer. Can the design principles of one field be easily transferred to another?

For me, there is no difference between architecture and other areas of design. Today, in my training anyway, I would combine things. And although I've spent most of my professional life in industrial design, I've never regretted having architecture as my background.

But specialization is now very much in demand ...

I can't recommend this specialization that has now taken root. The development of new technologies and materials will become increasingly important and I believe that the future lies in technology design and interdisciplinarity.

The beauty that emanates from functional things applies to the whole of everyday culture and is something that needs to be understood again today.

Above all, I expect the future to meet the economic and ecological requirements that are becoming increasingly important in their entirety! In short: sustainability in harmony with ecology, economy and social responsibility.

Does design always have to make a positive contribution to people?

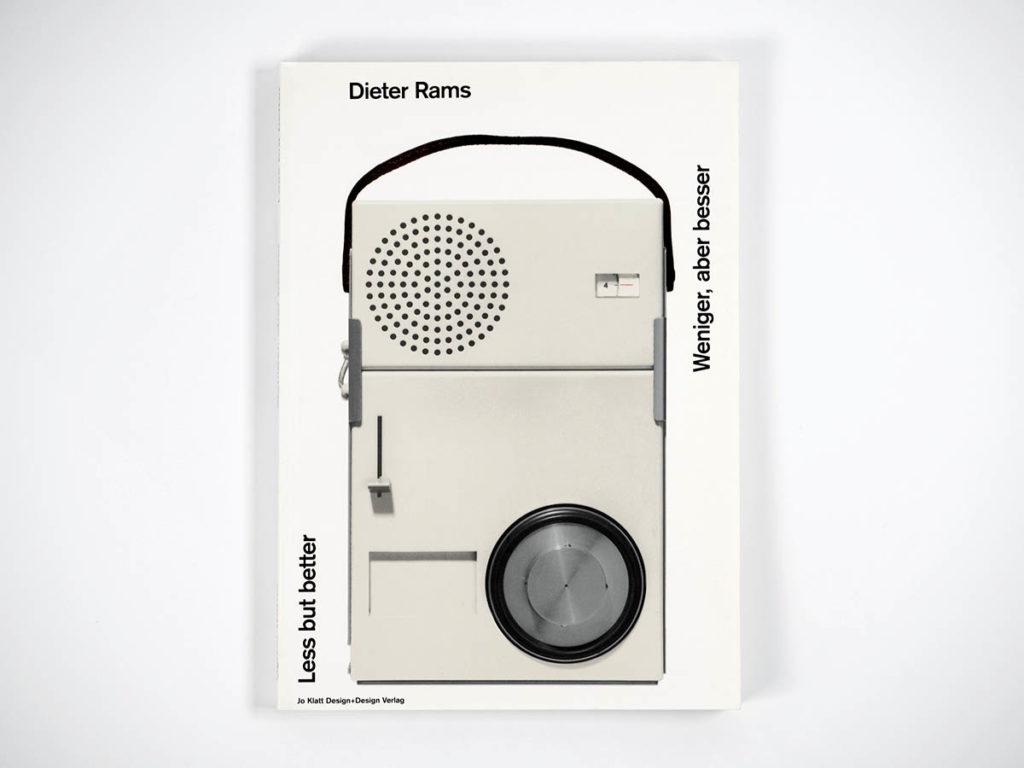

Yes, this is also one of my theses: "Less but better" refers to the fact that today we need fewer products that constantly stimulate the desire to buy, are barely usable, are thrown away and replaced by new ones. We need fewer products that break down early, wear out and age prematurely. Instead, we need more things that actually are and do what users should expect of them: Facilitate, expand and intensify life.

Do you take your inspiration from nature and your surroundings?

It's essential to walk around with your antennae up all the time, you have to absorb everything, not just the things that nature keeps showing us. And good repetition is sometimes also beneficial. We forget far too quickly and find it difficult to learn.

What advice would you give to young designers?

If a designer can't work with others, whether they are engineers or other people who are important for production, then they are already lost, all their creative ideas are useless.

Only if I listen to others and take on board their arguments will they also be prepared to take on board mine. Sometimes it's as simple as that. So that's the bigger requirement for young designers, of course they also need luck and, in the design sector, above all stamina, so that they don't fall over at the first wind.

Is the content more important than the tool or the way it is executed?

Yes and no. Even the most meticulous design becomes implausible and ineffective if the technology is unimaginative, the production inadequate or the advertising for it silly. We are still in a dilemma, and so is design, because it often takes refuge in superficialities and superficial, fashionable aspects that attract attention for a short time but are all the more ephemeral.

What needs to happen for people to realize this?

I always ask myself why people are not more aware of their environment, because we are experiencing increasing visual pollution. The question arises as to how much chaos we can or want to live with in the future. Appliances, the apartment or house we live in and the things we need should be so restrained and unobtrusive that we hardly notice them unless we need them. They should blend neutrally and casually into any environment. In such a way that they are not distracting and are a pleasure to use.

Giving products this aesthetic quality is and was by no means easy, and this must be made clear time and again. Unobtrusive, neutral design is not an end in itself and not a shortcoming, but a concrete advantage. I am convinced that many users (not consumers) will understand this.

The time dimension should also not be forgotten. How much waste can we afford at all? That's why I'm a little proud that the things I was responsible for are now largely valued by collectors and that the furniture is still in use today. After all, longevity cannot be achieved through design alone. Longevity requires the interplay of an intelligent product idea, successful construction, high manufacturing quality and well thought-out design. This shows that design can only be truly successful as part of an overall entrepreneurial performance.

If you could wish for the future that something that exists today would disappear, what would it be?

I have a very simple answer: the spectacular. The mendacious.