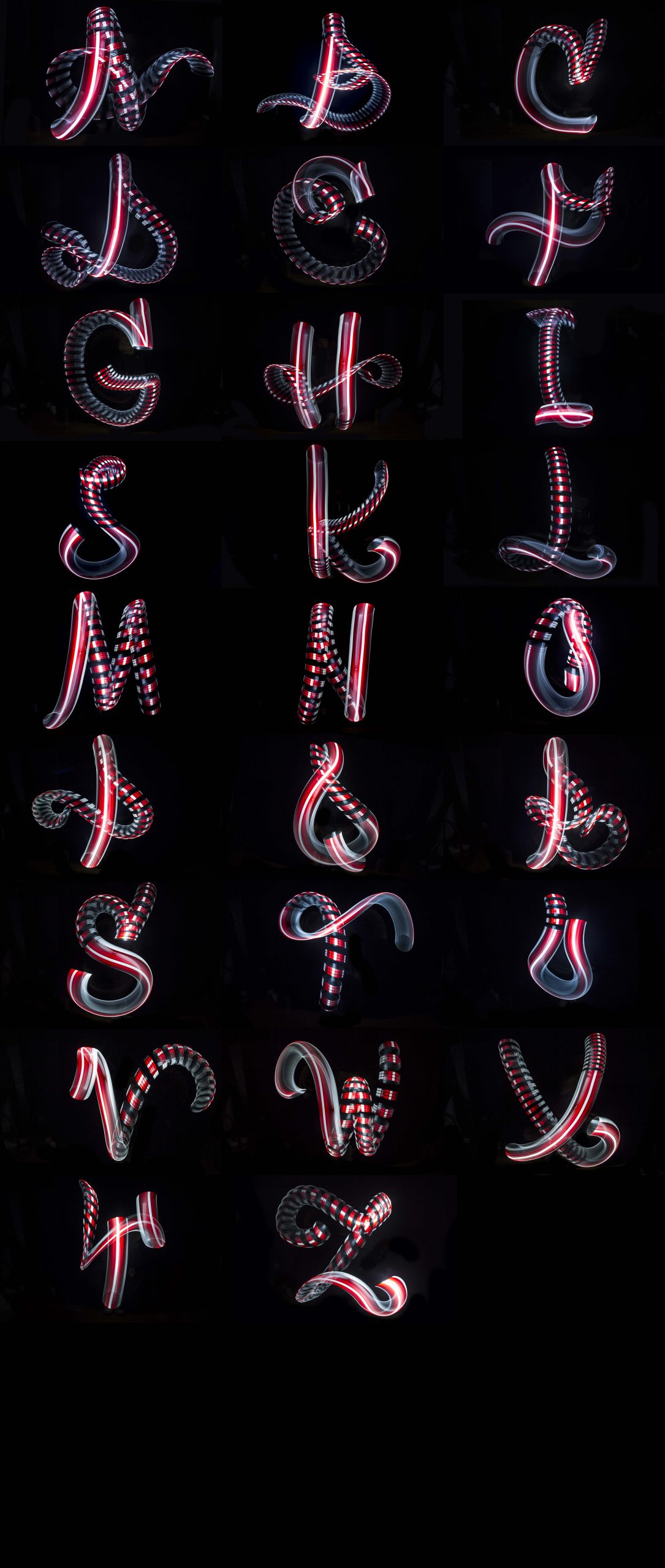

Christopher Noelle has been working with lightpainting photography in his pictures since 2003. In addition to typographic realization and the integration of 3D elements and robotics, the transdisciplinary approach, i.e. the fusion of different techniques, plays a decisive role in his approach. His portfolio includes both freelance and commissioned work of various kinds and with his constant drive for research and new approaches, he actually manages to blur the boundaries between the real and virtual worlds.

How did you get into light painting?

When I was shooting a graffiti documentary in Berlin in 2003, some writers took me on a "flashlight tour" and I photographed the light painting session, "virtual graffiti" so to speak. As I had been involved in photography for a long time before that, I immediately realized the potential of this technique and started to work extensively with light painting and to experiment continuously. The decisive factor for me at the time was that I had found a legal way to create temporary art in public spaces. I still love the option of doing it together with friends or on my own.

How can a layperson imagine your way of working, how do you approach a project?

At the beginning, of course, there was a lot of trial and error involved, but over time, the knowledge you've gained leads to a really efficient process. First of all, I usually make a fundamental decision about indoor or outdoor. For indoor shoots, I have a studio that can be completely darkened during the day. There I have a hodgepodge of light painting tools that offer many options: from acrylic blades to fiberglass brushes, self-made motors, adapters and tools, to light sabers and a modified pen plotter. When I shoot outdoors, I look for the right light sources beforehand so that everything fits into my photo backpack.

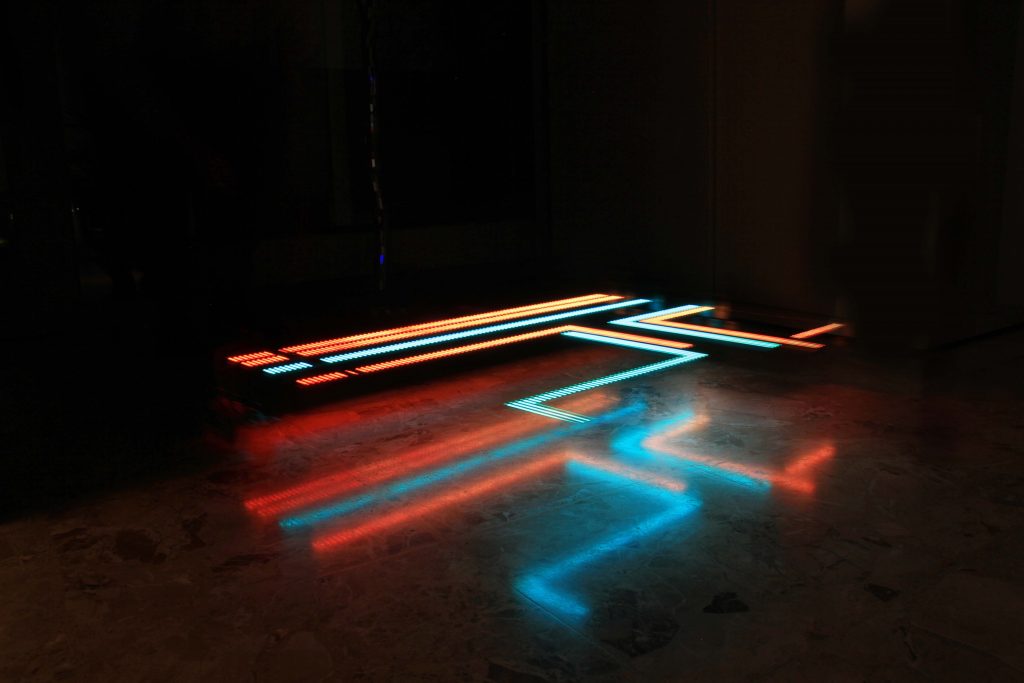

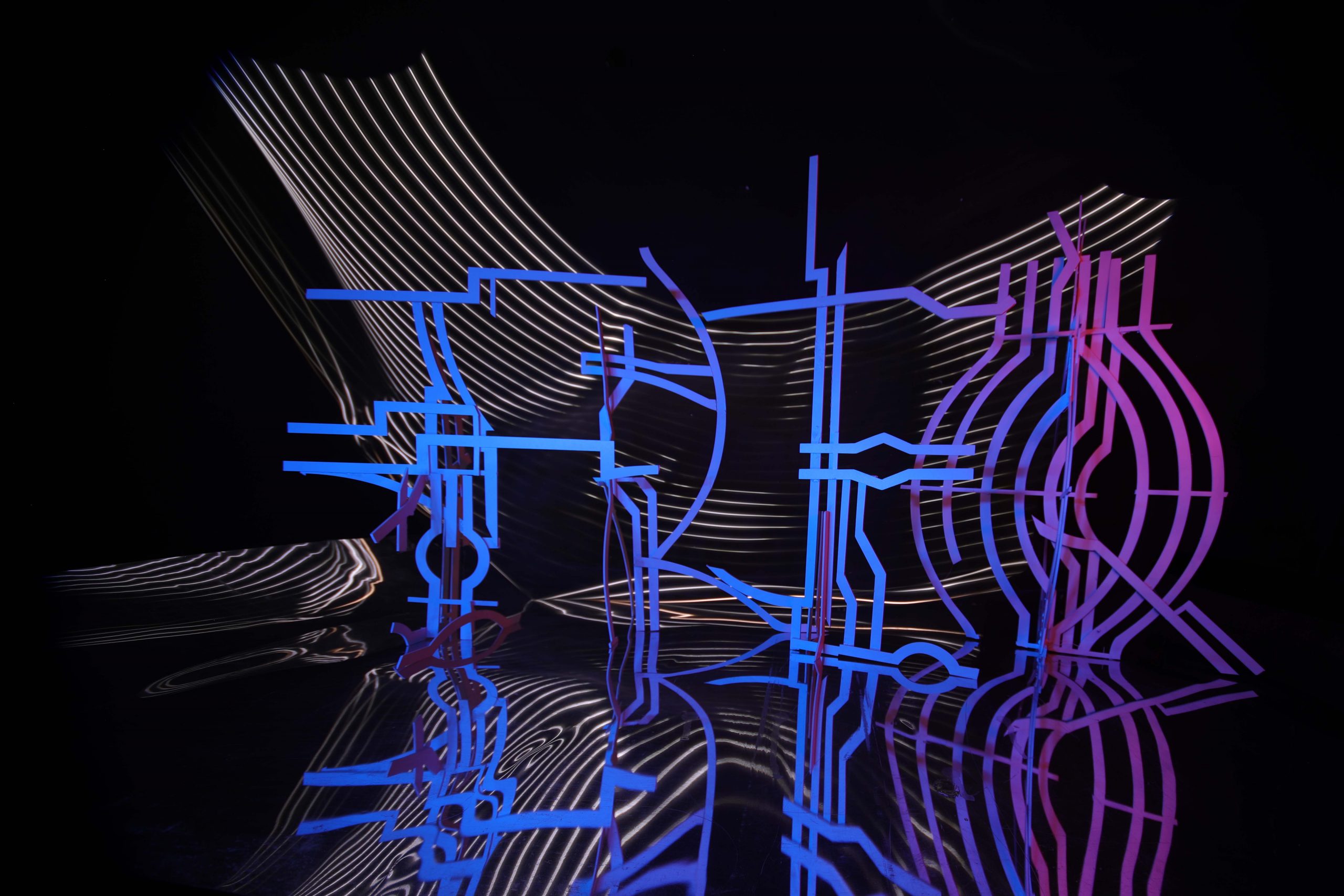

Sometimes it's a location that simply inspires me. But it can also be an image that I have in my head or, quite simply, a new tool that I first get to grips with in an experimental studio series. The maxim "less is more" applies to light painting. The picture needs space to breathe, especially outdoors, the surroundings naturally become part of the composition and too much light usually quickly leads to overkill. I like to call my way of working "Tai Chi in the dark", fluid movements and minimalistically used light sources under targeted guidance are the be-all and end-all. This presupposes that you know your equipment inside out, have the exact movement sequences in your head and know what works to make the picture a success.

What others are doing can also be interesting, for example I like to watch light painting technique tutorials so that I can implement my ideas even better.

What tools and technology do you work with?

The simplest light sources often guarantee the best results. I generally work with a Canon 5D Mk IV and various lenses (everything from macro to fisheye, 35mm, 50mm and telephoto) on a tripod with a remote shutter release. The camera is usually in bulp mode, at ISO 100 and the aperture depends on the ambient light. In other words, I activate the recording once, start shooting and only deactivate it again when I'm finished with everything. This can take anywhere from 5 seconds to over 30 minutes.

If you really immerse yourself in the subject matter, it's also a kind of creative sport. Which technique, which spot, which intention, which goal do I want to realize? Where do I need to light or leave black and how, what sequence achieves what? It's a lot about thinking ahead - and that combined with creative intuition is really fun.

What is analog and what is digital in your pictures?

Today, almost 99% of all light paintings are created digitally, as the choice of camera alone usually excludes the purely analog. The combination of digital technology and analog execution is therefore a transdisciplinary process that takes place in light painting. The actual supreme discipline (completely detached from the content/subject) is called SOOC (= Straight out of Camera), i.e. the creation of a real staging from an imaginary vision without computer help and post-processing.

As I photograph everything in both Jpg and RAW, I also use the computer when post-processing the RAW images, as I can still tweak the image quality there, which I really appreciate. Retouching rarely takes place, I'm more interested in color balance and contrasts or the right cropping.

You have a lot of experience, but is it really possible to predict what the results will be when working in this way?

Chance always plays a role, of course, but after almost 20 years of working with light painting techniques, I can predict with a fair degree of certainty what the result will look like and also how it can be realized or how it was created.

In workshops, for example, I start the seminar with a theoretical part in which I show pictures from the history of light painting photography and explain how each picture came about. After that, the participants are asked to develop their own ideas and to research online themselves in order to develop their own ideas. The question often arises: How was the image realized? This is where the wheat is separated from the chaff, because when analyzing light painting images you simply need a certain amount of experience to be able to recognize the individual parts and deconstruct the image. And I think it's great to see how different "newcomers" develop their own creative approaches and achieve really beautiful results.

With a little advice and assistance, most participants achieve usable results surprisingly quickly, which I often had to experiment with for a long time in the past. I would have liked to have had something like that myself in the past - that's why I enjoy passing on my knowledge.

Why do customers like Sony or Carhartt opt for light painting and not simply have a few graphics created?

With a photo, I can freeze a situation, a snapshot, and preserve it for posterity, so to speak. Dynamics, motor skills, spatial depth and reflection play a key role in light painting.

But chance also plays a role, because out of a series of 20-30 pictures, there are perhaps 10 pictures that I favor afterwards and that gives you more leeway when deciding and selecting the motif.

For me, it's a bit different with graphics, because I have a client, an agency, and they have a desired image in mind that needs to be realized as precisely as possible, which means that the playful, creative element can quickly get lost. But graphics can also enrich or enhance a photo. With light painting, I have the opportunity to stage graphic elements live in the picture, whether typographically, abstractly or experimentally, and I follow my intuition more than when I sit in front of the computer and push pixels. For me, this is simply a different, freer form of graphics.

What still fascinates and surprises you about light painting after all this time?

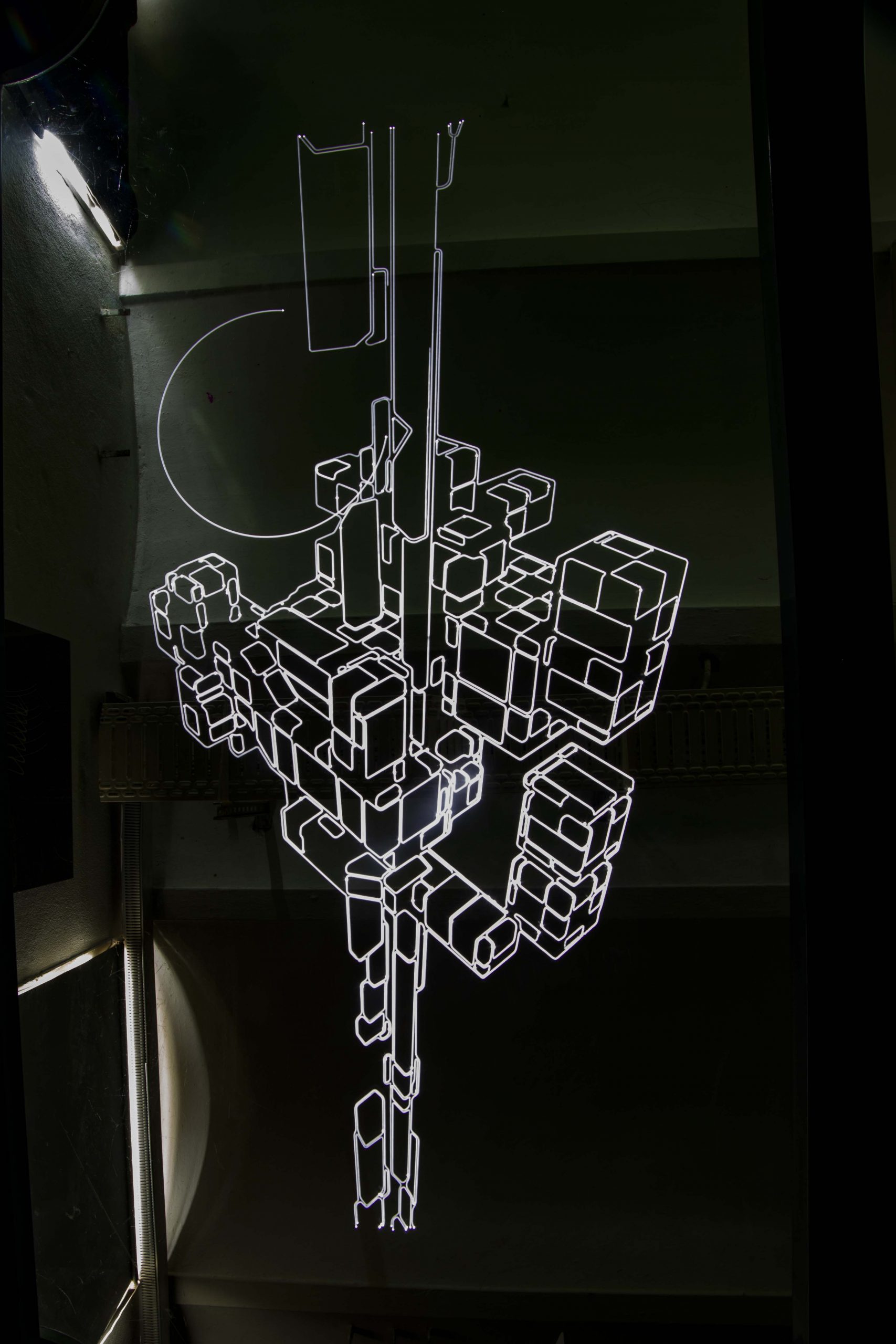

After so many years, it's still great to come across new things that fascinate and motivate me. I'm interested in discovering cross-media techniques, such as the use of a Kuka industrial robot in collaboration with the robotics lab at the University of Art and Design Linz or on a smaller scale, such as with my converted pen plotter, which is actually made for tracing SVG graphics. Here I can use my DIY tool - a pressure-sensitive fiberglass LED pen - to create a vector plot from a 3D graphic and take a long exposure from underneath the glass plate during the printing process in order to repurpose the printer as a light-painting robot.

For me, it's all about recognizing the different angle, the unexpected perspective, which opens up new possibilities and thus keeps the fascination alive.

You can also find an article on the fascinating work of Christopher Noelle in Grafikmagazin 02.22.