The conviction that idealistic goals lend great strength to one's own work has guided designer Nina Reisinger in her design practice for years. In her teaching activities, including at the Berlin University of Applied Sciences, she wants to convey to students that they can literally help shape the world with their design profession - and that they can use responsible, ethical principles to do so. However, she recently gave the keynote speech "Ethics & Design: The Grid is Dissolving" not in the lecture hall, but at a conference on international political design. This allowed her to do what she loves most: step out of her own bubble.

This article is from our issue 06.23 "Design in space"

"Everything was designed."

Interdisciplinary thinking is a central concern of her work as a designer and lecturer - she was therefore particularly pleased to be asked to take part in a conference on international politics. One of the initiators, she explains, is very interested in politics in design and its infrastructural and social processes, hence the invitation. "The question of how deeply I can delve into the topic and what ideas exist about the concept of design was really interesting for me," says Reisinger.

The full title of the lecture "Ethics & Design: The Grid is Dissolving. How to Implement Ethics in Design by Unlearning (Design) History" refers metaphorically and literally to the grids of our society. Nina Reisinger begins with a basic examination of the concept of design in order to get everyone on board: "What is design anyway? We might think of objects such as chairs or cars, perhaps Bauhaus or Vitra, or designed objects such as websites or posters, Amazon navigation or Tinder. We are surrounded by design 24/7," she explains to the conference participants. "Everything has been designed." She defines design as a craft that has always been at the service of capitalist logic.

Design has had to adapt to technological and cultural changes more than almost any other discipline. In our increasingly fast-paced information age, it is the designers who codify virtually all types of information. Ethical issues are always involved, and Reisinger also addresses the fact that even supposedly good design - such as an advertising campaign or a dating app - can make us feel inadequate and lonely. Not to mention the completely new questions that arise through the use of AI tools.

Is innovation always really better?

Nina Reisinger also mentions a certain techno-optimism in this context: "When we talk about innovation, we usually automatically assume that it is something good. But is it really? Isn't it rather the case that an innovative product serves capitalism even better? Progress is often sold as a savior, but behind it often lies the drive to remain competitive."

Reisinger is aware that not all participants may be able to follow her comparison of a grid with the capitalist system in the context of the conference. "Of course, questioning the ethical necessity of a seemingly lucrative design contract is often radical and defies any market logic. Because when we look around and see how the place is burning, we already have a purely theoretical answer: there should be less design overall."

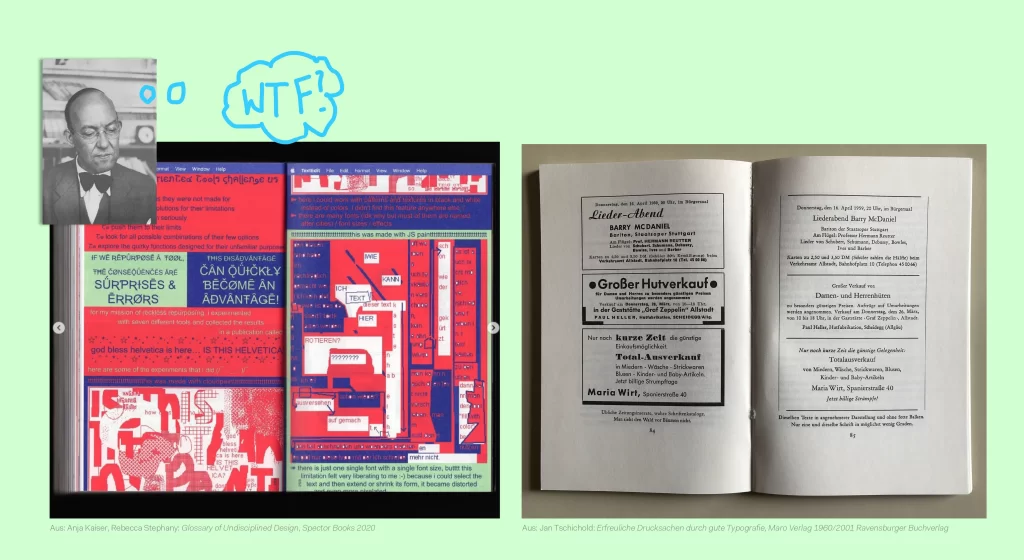

Her understanding of ethics in design was interwoven with social issues early on: one of her older seminars, which she held together with her longstanding colleague, the artist Micha Wille, was called "How Patriarchy and Capitalism fucked up my life and what I will do about it". Nina Reisinger had already been driven by the desire to deal with the proverbial creative leeway of strict hierarchies much earlier, ever since her diploma studies at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna in the noughties and her first commercial agency jobs. In her lecture, she talks about how every small child learns to think outside of a discipline - and unfortunately later forgets to do so again, as pigeonholing is part of socialization. During her studies, she understood design as a craft, "a skill set that has been taught in a certain way for over 100 years, with the same idols and role models, the same dos and don'ts". Although there were subversive counter-movements to many strict design luminaries that reached the mainstream like punk or Memphis, the basic framework of the design doctrine was always clearly outlined. "Especially in typography, there are many rules that can also be very intimidating," says Reisinger.

"I see the world as a garden"

"Precision was so important in my studies that I was downright afraid of serious typography. I wasn't so keen on precision, I was more impulsive. That's why I somehow felt out of place in the world of design."

Today, she is glad that there are certain rules for orientation and legibility, but she also likes to break them from time to time. And she always combines her teaching with practical ethical principles that show students the power of design. She explains that she is often the first to confront students with ethics - the curriculum tends to focus more on technology, UX design and an introduction to the agency world. "In my courses, I always say: 'You can say no to jobs, you are free to decide where you work. You can change things. Realize that you are shaping the world with your job. And the world you shape is the world we live in."

She repeatedly gives the students literature tips to make them more articulate, for example from the Dutch publishing house Valiz, which publishes insightful books on social design and ethics. "Another important source for me was form, which unfortunately no longer exists in print. Or Missy Magazine, which was designed for a long time by my good friend Daniela Burger." She doesn't pursue classical scientific work because that was never part of her studies. "I see the world more as a garden from which I pick what I need for my teaching work."

Nina Reisinger also wants to provide conference participants with a kind of vocabulary so that they can name where it comes from, what design we like. The sources she provides are intended to break up the stereotypical patriarchal discourse. She wants to offer other perspectives that may not answer everything, but raise the right questions.

Her message at the International Politics conference is not much different from her design theory seminars: "The moment I talk about ethics, I am already in a political field. Then I'm talking about inclusion or decolonization, about patriarchal structures. Of course, teaching is always political."

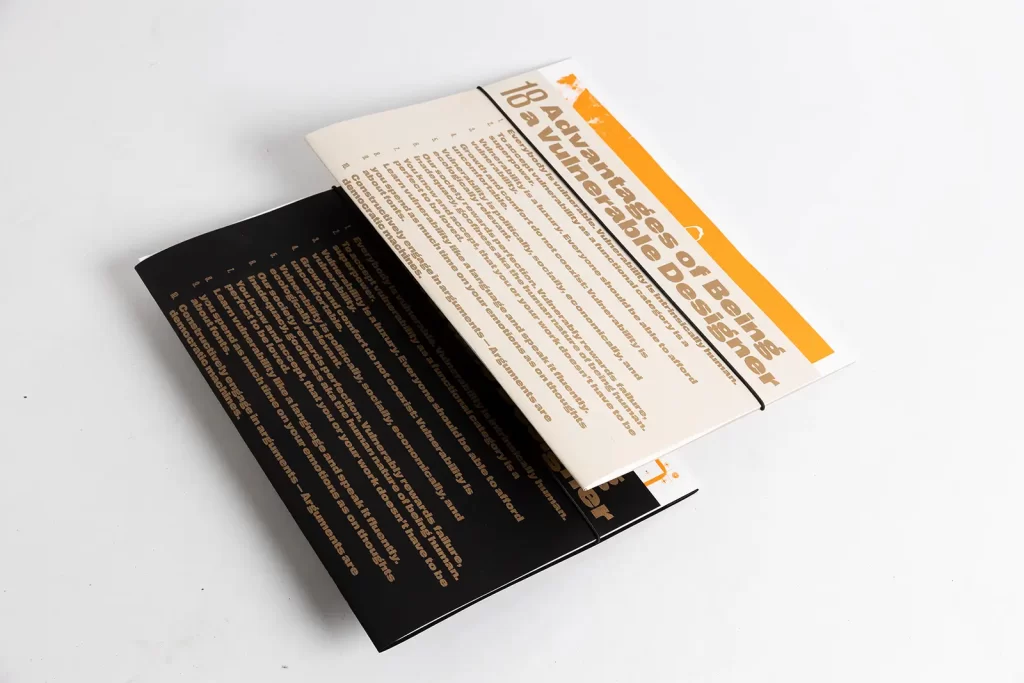

So what does it mean in concrete terms to break up the grid? Nina Reisinger sees great potential in allowing disorder, which is sometimes even necessary in order to be able to work creatively. "In other words: fluidity, openness, humor, fewer hierarchies, more space," she says, "and above all, vulnerability." This is also the focus of her latest seminar in collaboration with Micha Wille, which began in October at HTW Berlin: "Strategies of Vulnerability in Design", the semester project revolves around the challenge of remaining vulnerable in the face of capitalist logic. Remaining open in the face of a certain position of power as a lecturer is not always easy, she says: "You have to be sensitive to this role, especially when students open up to it with their personal stories, such as stories of classism or migration."

In order to reflect on her own effectiveness, Reisinger sets her students the task of writing their own design manifesto - and thus internalizing that it is easier and, not least, more resource-efficient to create a design product from the outset with a focus on people and according to ethical principles than to apply improvements to an existing product afterwards. Her message to the conference participants: Clearly, the idea that ethical design should detach itself from capitalism is blatant. And of course it raises the question of how to earn money with it. "But idealism also conceals the power to develop good ideas and boldly go in a certain direction."

You can find out more about Nina Reisinger's exciting work here.

Order our issue 06.23 "Design in space" here

If you don't want to miss any more news from the world of graphic design, please subscribe to our newsletter.

Photos of the project "The Grid is Dissolving: Strategies of Vulnerability in Design": Yu Ling Cheng, Thereza Menclová, Laura Wolf