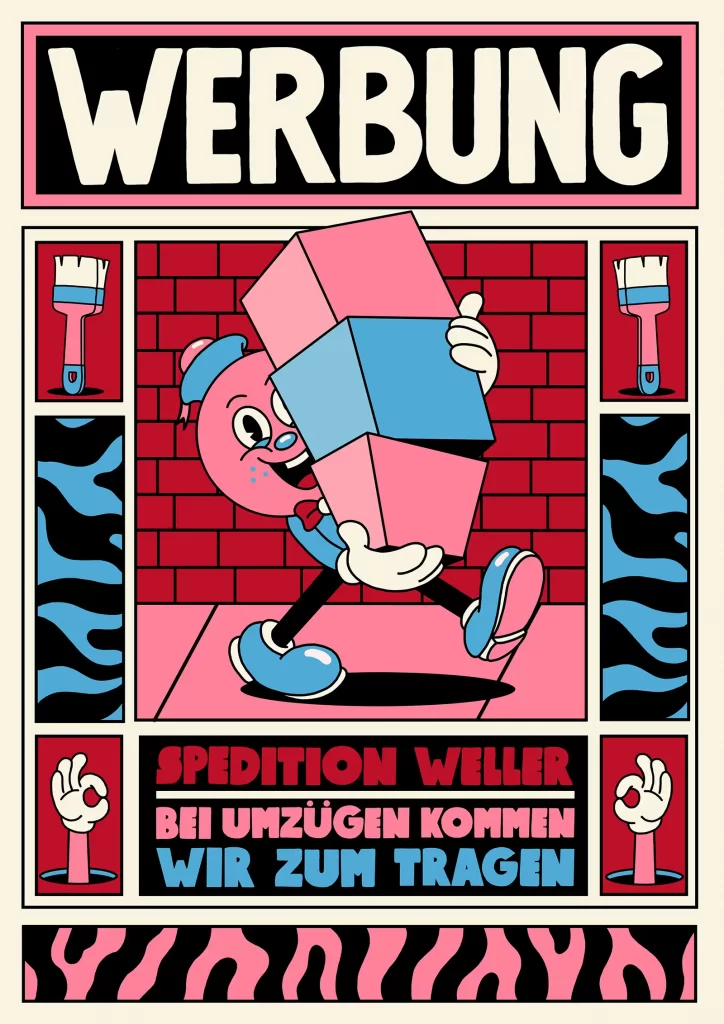

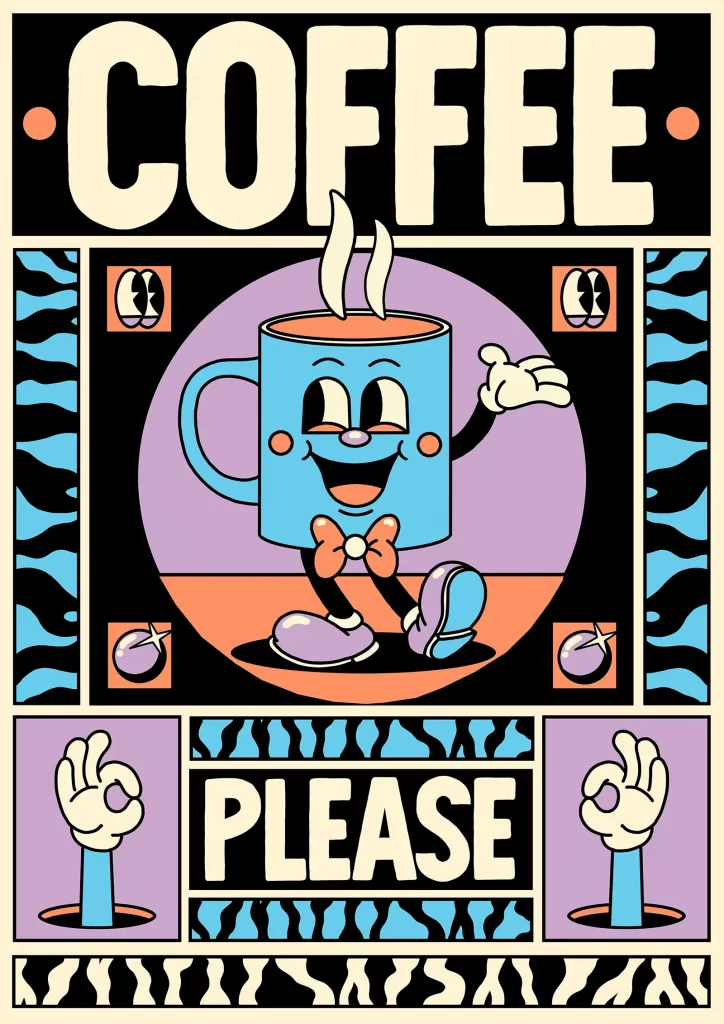

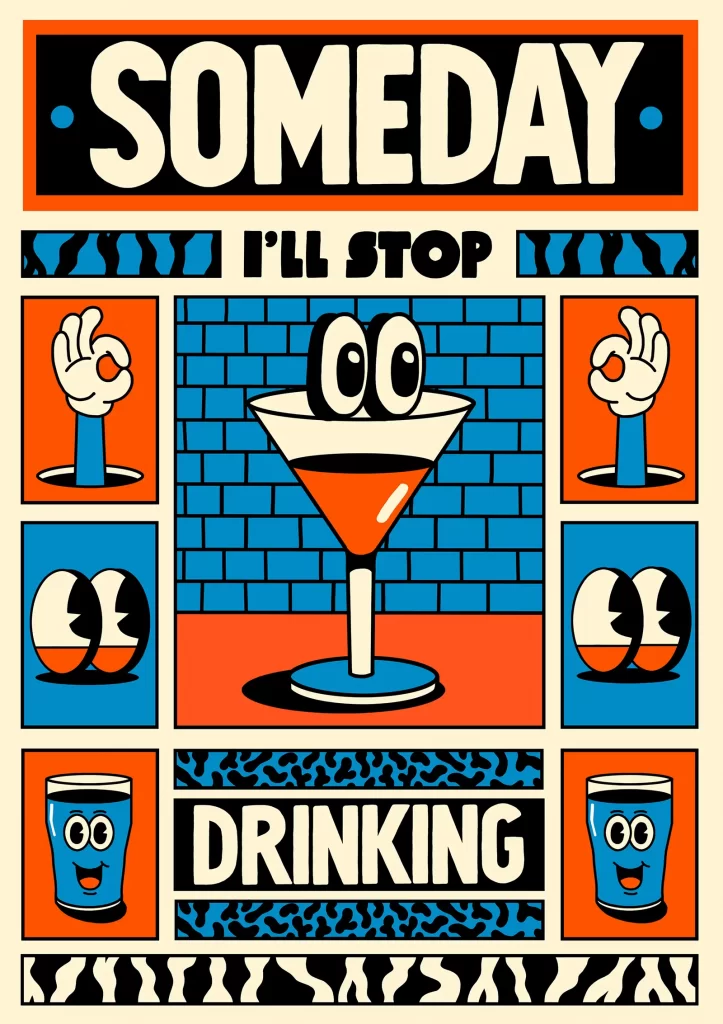

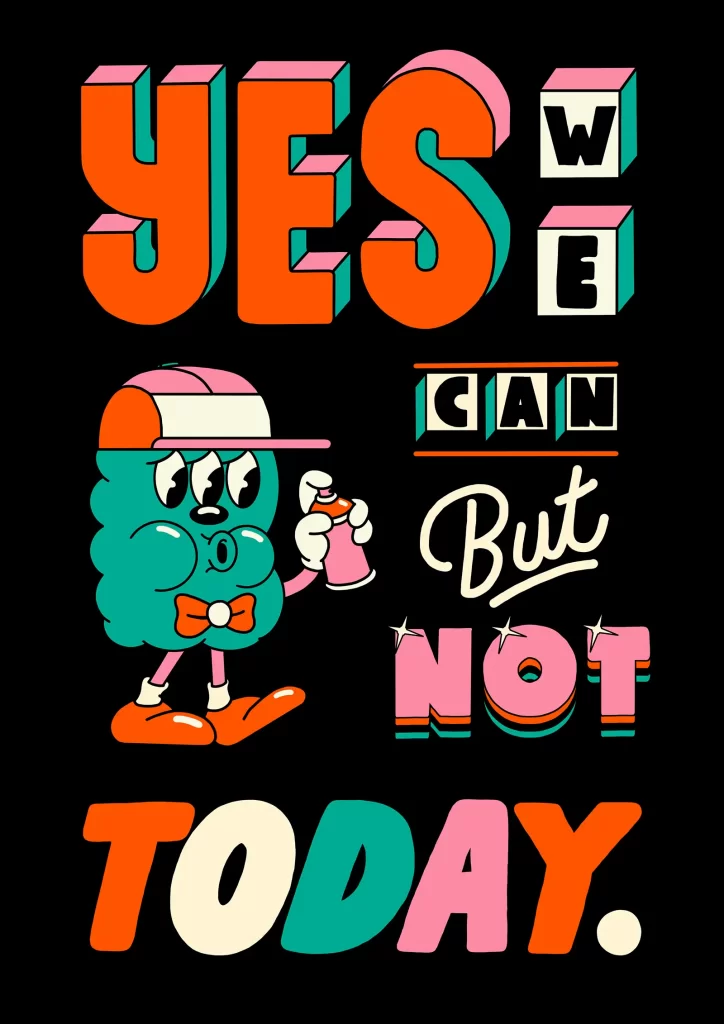

Yeye Weller's illustrations are loud and colorful and their cheerfulness often conceals a good dose of irony. Well over 115k followers on Instagram enthusiastically comment "Awesome" or "Looveee" and brands such as Adidas, Netflix and the New York Times have long since discovered the illustrator for themselves. However, the conversation reveals a very pragmatic and reflective artist who relies on classic design craftsmanship and does not want to be deprived of his own creative freedom despite all his success.

Yeye Weller, how did you get into illustration, what excites you about it?

Good question, which of course is not so easy to answer. You don't just open a door at some point and say: So, from now on I'm interested in art.

I wasn't really the kind of kid who sat at a desk at home all day drawing, but I think I've always had an enthusiasm for design and an appreciation for aesthetics. It started as a little boy with the fascination and collection of beer mats, later I diligently collected stickers from skateboard companies. And when I was 14, we founded our first "skate company" and sold self-printed shirts to our friends and schoolmates in our small town. Even though I didn't do much illustrative drawing at the time and tended to do more classic graphic design, this phase was more or less the foundation stone for my later development, because shortly afterwards a school friend gave me a cracked version of Adobe Photoshop and things took their course.

How do you work?

I actually always follow the same procedure when it comes to realization. First of all, I come into my study and turn on the music. Then I actually start in the classic way with paper and pencil and create a few rough sketches, before finally developing a concrete layout step by step with the pencil.

Then I scan it in and draw it cleanly with the help of a graphics tablet and Photoshop. I deliberately avoid any effects and digital bells and whistles: one brush tip that is always the same, black outlines, 3-4 different colors and the same graphics tablet and the same "old" scanner for over 10 years.

As much as I like to try things out in the creative process and develop myself further, I work almost exclusively with techniques and equipment that have proven themselves over the years and with which I am familiar.

Your work is colorful, flat and somewhat retro in a quirky way. How do you develop your image ideas?

I love the designs of old matchboxes or the layout of classic beer labels. Designs from a time when not everyone with Photoshop on their computer was also a designer and where you didn't download two fonts to design packaging for a hand soap in one morning. I like it when you notice that the font, design and illustration speak the same language and that's exactly what I try to take to heart in my illustrations. Of course you can call it "retro", but I would prefer the term "classic", because I believe that good designs never really go out of fashion. That's why I also try to keep the "classic" alive in a new design language and combine layouts and cartoon characters that are actually familiar from the middle of the last century with modern patterns, colors or image ideas to create a harmonious overall picture.

Your characters seem childlike and nice, how does the sarcasm come into play?

The sarcasm was actually just a means to an end and pretty much born out of necessity. I really resisted working in English and using hashtags for a long time. I would have liked to have done this to this day, but then I would probably still be selling my illustrated DIY booklets at cost price, eating canned ravioli and only have one pair of jeans in my wardrobe. As long as you're young, this is a charming way of life, but somehow you don't just make art for yourself, no matter how "underground" you feel.

Success and validation are ultimately the nicer feelings. So I had no choice but to switch to English and use hashtags if I wanted to be noticed by the world. However, the new approach felt very strange to me at first and even though sarcasm and irony have always been part of my work, I initially only used this stylistic device to suppress my initial insecurity. Over time, however, this developed into a visual language that is not always unambiguous, especially in the combination of words and images, which is perhaps why it is so interesting for me.

What inspires you?

Inspiration is of course a very elastic term. Personally, I think answers like I'm inspired by life, nature or that one Bob Dylan song are nonsense. Of course, these are all beautiful things, but the only thing that has really had a significant impact on my illustrations is the work of other artists or designers.

For example, as a child I was a big fan of the Beatles' animated film "Yellow Submarine". I must have seen the film 50 times, but I was always amazed and to this day I love the colors, the characters and especially the visual language of Heinz Edelmann. Through such "role models" you develop a personal aesthetic over the years and (as a result) constantly use various fragments of other illustrations to ultimately find your own style.

You sell your work as book and screen prints, sell pins, cards and key rings, but you also illustrate for clients such as Adidas, Netflix, McDonalds and the WWF. Your style is very distinctive, does every customer simply always get Yeye Weller or how much do you adapt to customer wishes?

Yes, actually the customer always gets Yeye Weller. In principle, I've always tried to only accept things for which I don't have to "bend" myself artistically. From today's perspective, that all sounds very decent and self-confident, but the bitter truth is that I received Hartz 4 from the job center for the first 3 years after my studies and was annoyed several times afterwards about having turned down lucrative jobs for artistic reasons or vanity. Nevertheless, I believe more than ever that it was precisely this phase that gave me a security in terms of style and content that I might never have found otherwise. Because I didn't have to constantly adapt in order to make a quick buck or please the client, I was able to take the time to work on what really fulfills me every day.

How much is an illustrator an artist and how much a service provider?

Unfortunately, there is not much left of my idealistic approach. As sad as it sounds, I now feel 80% service provider and 20% artist, and to be honest, the stress usually outweighs the joy in my day-to-day work. Of course, that's complaining on a high level and you should always remember what a wonderful job you have. When Jimmy Kimmel gets up in the morning and is once again not in the mood for his job, he imagines that he is a seven-year-old boy and has won a competition to be Jimmy Kimmel for a day. I like this idea and even if I'm not Jimmy Kimmel, it helps enormously to realistically categorize my position.

Because of course it's extremely flattering to work for Netflix or Adidas and I always like to remember how the first request from the New York Times arrived in my mailbox. A moment of pure bliss. But at the same time, it should be clear to everyone that the bigger the client and the more commercial the assignment, the more people want to have something to say and expect it to be realized according to their ideas, and with every additional correction loop, artistic freedom becomes increasingly stunted. That's why it's still important to have the cheek to turn down lucrative offers and regularly take time out for your own projects. Get back to your roots and get back to doing what you enjoy.

At first glance, many of your works seem rather under-complex. Is it like in the circus when silly August falls down clumsily and slips and nobody realizes that there are actually a lot of acrobatics and body control behind it? In other words, how great is the art of touching people again and again with just funny eyes, shoes, hands and a bit of typography?

I really can't say that there's much planning behind my illustrations. I actually always trust my gut feeling and, to be honest, the best ideas usually come completely spontaneously. But perhaps your comparison is very apt, because it's precisely through years of doing things that you gain a certainty that allows for this spontaneity and ease. I've never thought about it before, but I like it.

Are there times when you can no longer see chubby-cheeked, laughing little men with big eyes?

That would be really sad if that were to happen at some point. Of course there are times when you can no longer see some projects, but I actually really enjoy coming into my office every morning. Even if the work process itself is sometimes exhausting and requires a lot of concentration. I love my job just for the moment of completion and the satisfying feeling of a coherent result.

However, there is a moment almost every day when I stumble across the wonderful work of various illustrators around the world on the Internet and think to myself, why don't I make such cool shit? Helmut Dietl once said that as a director he hardly ever went to the movies anymore. It depressed him, either because the films were so bad or because they were so good, but not by him. It's not quite as bad for me. I love looking at other illustrators' work, without a hint of envy, but to be honest you often feel "so small with a hat" afterwards.

We don't all have so much to laugh about at the moment, but what are you still looking forward to?professionally, I have to say that you always look forward to finishing and starting a new project. There are some great projects for our store coming up soon that I'm really looking forward to.

You can also find an article on Yeye Weller's work in Grafikmagazin 01.22. This issue focuses on "Illustration" and there are many other exciting illustrators and artists to discover on 20 pages. The interview was conducted by Christine Moosmann.

You can find more illustration topics here ...