Paula Scher has shaped graphic design over the last fifty years like no other designer. Many of her visuals are still used unchanged decades later, her signage systems and graphics are present in public spaces and, as the first female partner of Pentagram New York and a long-time lecturer, she has shaped the design scene as well as the next generation. Even on her playlist, she often comes across record covers that she herself designed in the seventies, as she amusedly recounts. It is no exaggeration to say that Paula Scher is a design legend. But how do you get to this position and how do you manage to create things over such a long period of time that are relevant, contemporary and timeless at the same time?

Christine Moosmann spoke to Paula Scher about her beginnings, about role models, about successful projects and unpleasant customers and about what print communication needs today.

Paula, you have been a successful graphic designer for many years, how did you perceive the industry when you started out?

It was quite easy to get a foothold in the profession back then, the industry was open and accessible. People were just starting to understand what graphic design was. Not the general public, of course, but there was a design scene in New York and Los Angeles that was influenced by Europeans and Swiss Modernism was beginning to permeate American design culture in the fifties and sixties. The local graphic design industry was very small at the time and was perceived more as commercial art. In the Midwest, for example, there were people who made what today would be called naïve art, but they created images for industry, so they were commercial artists. But they had enormous craftsmanship ...

Like sign painters?

Exactly, the sign painters, people who created murals or lettering, some of them were beautiful. In a way they were guileless, they were creating art for commercial purposes and they had no problem with that.

I can remember what it was like when I started out as a graphic designer in the music industry. Back then, as a graphic designer, you were competing with the printers because they were what was called a "graphics house". You had something printed there and you got the design as a freebie.

I was very lucky though, because working for the music industry I got to design the big 12 x 12 inch record sleeves. They were basically early marketing pieces that went out all over the world - no testing, no market research, nothing. If people liked the cover, it sold, it was as simple as that. (Laughs). That was my introduction to design. On top of that, I was in a big company and was able to observe how decisions were made - everything I learned about being a designer, I learned in those ten years in the music industry. I've benefited from that for the rest of my life. That's also where I made all my typography discoveries, because I just produced a lot of designs. If the result was terrible, then I learned from it. Today you no longer have that luxury.

So the first few years were literally "learning by doing"?

Yes, basically I learned this job by doing it, by trying things out, by looking around and drawing from many sources. I was responsible for around 150 covers a year. What helped me was that I quickly grasped the politics behind the business decisions. I knew what the company expected, knew the budget and could therefore weigh up what was feasible and what was not. I focused on making the important studio bosses happy and in return they allowed me to do my covers, even if they were politically questionable. If I did it cleverly, they rewarded me by letting me do covers for people the label wanted to drop anyway or for acts that were so small that no one was interested in them anyway and that's where I could do my real creative work.

So I tried to find a balance between the things that had to be commercially successful and the things I did for myself.

Did you have a vision of what you wanted to achieve as a designer right from the start?

I actually discovered graphic design at the end of my sophomore year at Tyler School of Art. I was terrible and took every class I could think of: painting, drawing, metalwork, sculpture and ceramics. I thought I was going to be an illustrator, I had no idea about typography. I could draw a little, but mainly paint. My teacher at the time, Stanislav Sigorski, a Polish illustrator, saved me. When we were supposed to do illustrations for books or record covers, he observed how I cut out letters from newspapers or magazines and pressed them onto my illustrations. He said: Don't illustrate with letters! He had a strong Polish accent and what he said was always short and very simplified. At first I thought he meant "illustrate the writing", in the sense of decorating it. But then I realized that he was trying to make me understand that type has a form and with this form you could make a statement and communicate.

So I understood that graphic design was not as accurate and sterile as I first thought. And that was the beginning of everything for me.

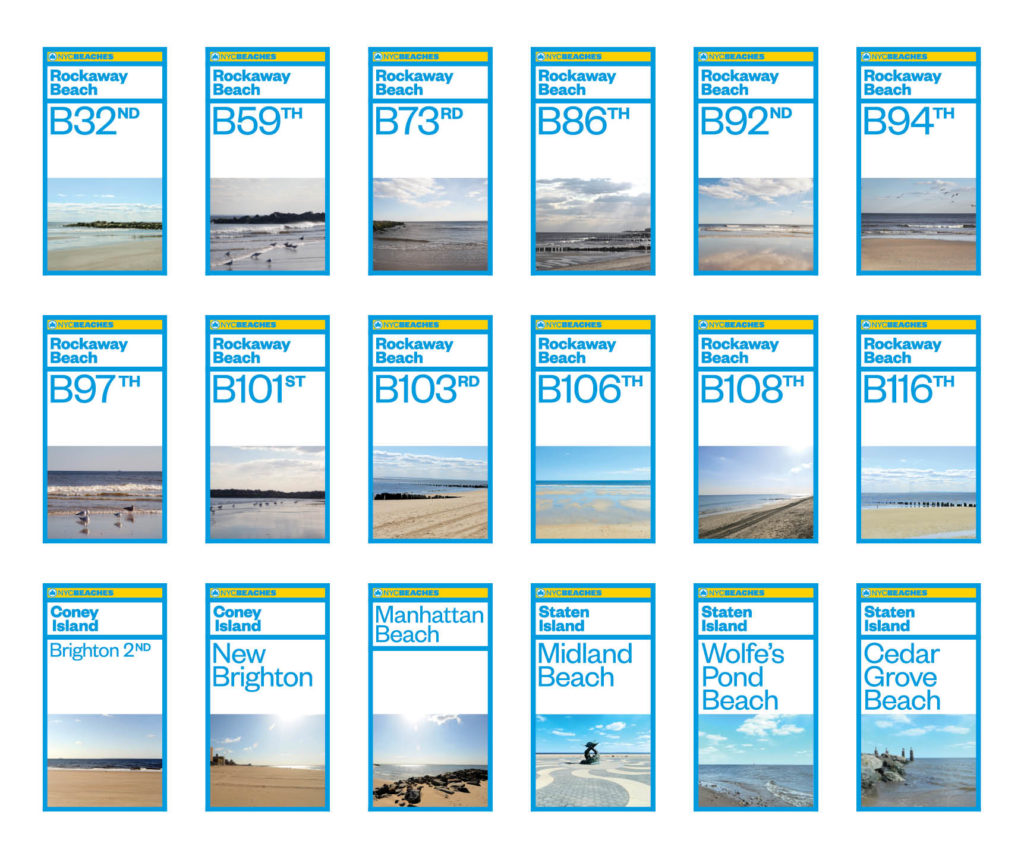

Architect: Rogers Marvel Architects, Design: Pentagram

Do you think that students used to have more freedom to try things out and find their own way?

Not really. I teach myself, I've been running a senior portfolio course for 37 years and I pass on what I know. It's mostly about images, which are made up of many different components, and the aim is to solve problems. So it's not dramatically different from when I was at art school, except for the technology. Technology allows us to do more in less time. The area where I think the industry has changed the most has to do with time. Thanks to computers, you can do more, you just have to know what you want and the computer does it. In the past, you had to do everything yourself mechanically and that often took hours.

This has led to another change in the industry. Because the designers used to take so much time to do their craft, it shortened the time that the marketing people could spend on the project. When designing an opera album, for example, the libretto and images of the opera were also included, but both had to be compiled by hand. And everything had to be proofread very carefully, because what went to print was still typeset manually back then. The proofreaders cut out the spelling mistakes with a cutter and pasted the correct letters back in. That took an enormous amount of time.

Today, projects take just as long as they used to, but the marketeers now take up most of the time.

In this sense, the new technologies put designers under pressure. Your career sounds more like a journey of discovery ...

Well, that's still the case. When I started working with computers, the whole thing was still very limited. For example, you couldn't incorporate slanted fonts into the designs, you had to print out the letters and rescale them. That was pretty crazy.

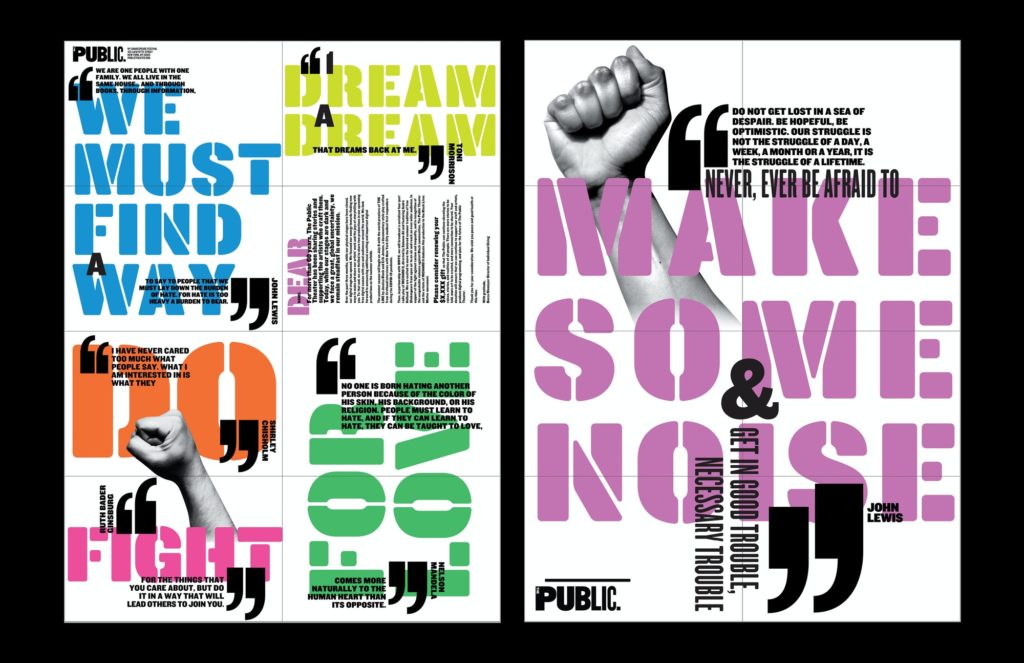

Right now is the most sensational time for typography that I have ever experienced. The tremendous craftsmanship that designers have developed, combined with the technology available, is producing outstanding results. What designers with an understanding of form can do today is nothing short of miraculous.

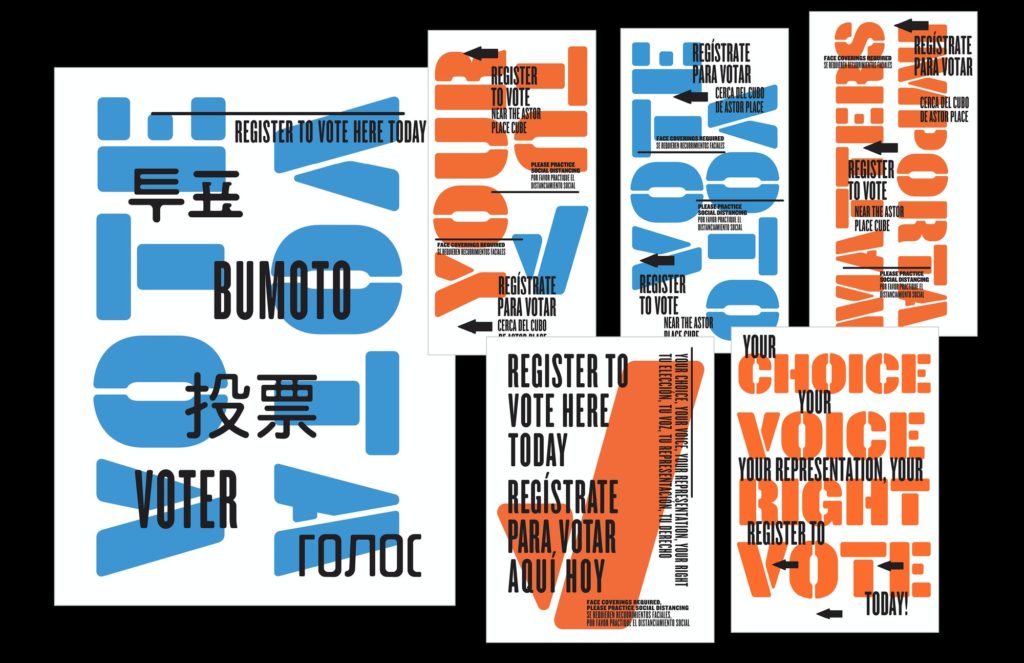

Today's technology also enables me to do much more spatial work. I started designing signage, wayfinding systems and spatial graphics a good 20 years ago. Basically, I married design and architecture by creating visuals for spaces. Seeing what the space would look like, I couldn't do that before. All these wonderful programs, I can't tell you what that did for design!

Of course, there were spectacular designs before, in the forties or fifties. I was sitting in the PAN-AM lounge at La Guardia airport the other day, what beautiful architecture and to know that these crazy lines and shapes were created without computers. When there were no computers, you had to be a genius to create something like that

Conversely, does this mean that anyone can become a creator today just because they have a computer with sophisticated programs?

I don't think the level of mediocrity has risen. I think that the ratio of really good work compared to bad or mediocre work has always been balanced historically. Today there are simply more designers, so you find more good work, but the ratio has remained the same.

If there is so much more of everything today, how do you find the really excellent work?

Oh, they always come to the surface somehow. Sometimes you see them in public, but more often they come from the design scene itself. They just pop up, someone calls you or sends you an email. Sometimes I also see great things at design awards or I stumble across them in the Type Directors Club yearbook.

Where do you get your inspiration from?

Hm, good question. Of course from my business partners, I get a lot from them, they are very good and I learn a lot from them. I also learn a lot from my team. But what inspires me most are the projects I work on. When I get a project on the table and I look at the client and see a lot of possibilities, then everything suddenly becomes very exciting. If I get a client who doesn't allow any leeway, then it's depressing.

Architect: Project Design Associates, Graphics: Pentagram (Paula Scher)

Will you accept the order anyway?

Yes of course, after all we need the money.

There are designers who turn down jobs or clients they don't like.

Oh, I don't believe them! (laughs) I think they need the money too.

But of course there are things I wouldn't repeat. There are types of clients that I don't like working for. In the field of graphic design, for example, these are developers of real estate projects or business reports, because both are very similar. In the case of a real estate company, I would rather work on the appearance of the building itself than on marketing and promotion. And in the case of an annual report, I would also be more interested in the CI than creating something that is only there to impress the shareholders. That wasn't always the case, but over time I started to turn down clients who wanted to do these things just to make a quick buck.

When you design the signage for a building, it's something permanent. It's much more fulfilling than coming up with advertising for that building. The same applies to annual reports. The value of a company lies in the company itself and not in the shareholders that the annual report is supposed to impress.

But many annual reports are true works of art. They are elaborately and beautifully produced, combining outstanding design with innovative printing techniques and craftsmanship. Doesn't that appeal to you?

Yes, of course, but the whole thing is nothing that lasts. You know, when I'm sitting in my car and playing my playlist, a little picture of a record cover that I designed in 1979 might suddenly pop up. That's incredible. There are designs of mine that are still on the market after all these years, floating around out there and enduring. The same goes for my visuals, some of which have been around for over twenty years, such as the design for the National Public Theatre, which was created 25 years ago and is still there. It's important to me to create things that last and continue to exist in society. That is important to me.

Design: Pentagram

As you say, many of your designs are still in use. When you design, is timelessness something that you think about from the start or does it just happen?

Hm, both. I did the look for the National Public Theater because I wanted it to survive. I wrote a book about that look, explaining what you can and can't anticipate as a designer. For example, when I created this design in 1974 that was going to work on the street, I couldn't possibly foresee that people would see it on Instagram many years later.

You can't see that coming as a designer and of course companies have ups and downs and staff changes can change a lot. The culture also changes. If you want to do justice to all of this, you have to keep things fresh and adapt. But elastic identities often don't survive because it takes a lot of time and effort to maintain and update them.

The better chance of survival is for identities that are monolithic, such as my logo for Citibank. It's blue, it's Citibank, they haven't changed the font and there are strict design rules. It's not terribly creative, but it's a bank and when you see blue, you know where you are.

What I also loved was working for the New School, because they had an in-house art department and allowed the people who worked there to expand the look. The CD was designed that way from the beginning, but it was the people on site who shaped it and gave the place a DNA. So there are different ways things can survive. That's part of the game and part of life.

Speaking of things that last. Do you think that printed communication is still important and has a future?

Of course. Some objects will never disappear, books for example. Some books are better read digitally, but others you want to own and keep forever. Things aren't garbage if you don't dispose of them.

I love reading newspapers, for example. But the piles of waste paper that accumulate at home annoy me. Overall, I read more newspapers today than before, but online. However, the appeal of the Sunday Times Magazine is not going away, I keep these magazines because they are great design objects. The same applies to the printed communication that we encounter in public spaces, on billboards or at bus stops. All of this is print and still has an important function.

In addition, the object-like quality of printed communication is becoming increasingly important. So if you want to launch a new magazine on the market, it will survive if it is beautiful. If it's a great object, the content is varied and intelligent and the overall package is inspiring, then there will always be people who love this object.

You have already done so many things in your life, is there still a dream project that you would like to realize?

I'd like to design movie titles, but apart from that I'm open to anything as long as I can see the possibility of creating something that will be great. That's all. With a few exceptions, most of my jobs are like that. What motivates me is the question, what could this thing be? It's important that I have the feeling that something is possible and then anything can be really great.

You can find the issue with this interview here in our store. You can find an article about the "Type is Image" exhibition here in our blog.